AMSTERDAM: Two victories, three defeats, a draw and fifth position in a field of seven. It is testimony to the depths to which Indian hockey has slipped that even a record as mediocre as this is seen as a leg up for the national game. Yet, last fortnight, as the Indian team left the Netherlands after playing the BMW Trophy at Amstelveen, located on the outskirts of Amsterdam, they had made a point. That despite everything that officialdom, petty politicking, lack of planning and patronage, and even waning popular interest had done to destroy the sport, India still possessed the talent to regain its original international stature.

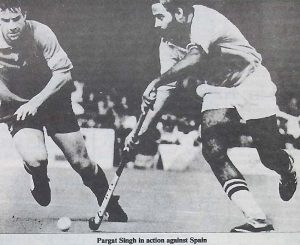

For too long have international hockey experts and writers lamented that fullback Pargat Singh could easily be acknowledged as the finest player in World hockey today if he were captaining a slightly better side. At Amstelveen’s Wagner Stadium, Pargat, showed his mettle not only by holding the defense together, but also by moving up into attack whenever necessary as his brilliant goal scoring thrust against Pakistan, resulting in India’s 42 victory, showed. He also played a stellar role in India’s victory against Olympic champions Great Britain— and in the fight back against West Germany that almost levelled the match. But often, he seemed a man too imaginative and motivated for a relatively mediocre Indian side.

There were other flashes of brilliance too. Young Jagbir Singh finally showed signs that he had emerged as the frontline striker India had needed for so long. With six goals Jagbir became the top scorer in the tournament, displaying opportunism and killer instinct, qualities Indian strikers have traditionally lacked. His spectacular lunge that deflected a Vivek Singh Sree hit into the Spanish goal was the kind of stuff Indian supporters normally see happening in the Indian striking circle. There was also a welcome return to form by left winger Thoiba who looked dangerous each time he broke free, though sometimes short of ideas after making the break.

The half-line too showed a new sense of purpose with Vivek Singh managing the midfield with imagination. What the Indian team lacked most of all was strategic thought. For example against Australia, who were the eventual winners, India after being twice in the lead, succumbed 36, failing to shore up their defence in anticipation of Australia’s counterattacks. Instead, the team got carried away, tried to match the Australians’ heightened pace and left gaps in the defence.

The Australian team was the quickest and fittest on show. Said team doctor Tom Henbest: “All our forwards and halfbacks can run the 100 metres in under 11.7 seconds.” In contrast, the Indian team showed weaknesses in both physical and mental preparation. ‘Said Hans Jorritsma, the legendary coach of the Dutch squad, about the Indian team

It needs a completely new physical fitness programme.”

Preparation, clearly, is the key. For example, so prepared were champions Australia that team doctor Henbest even brought along his own stretcher. The Indian team, characteristically, presented the other extreme. When they arrived in the Netherlands, lashed by icy cold winds and rain, the players did not even have any raincoats. ‘Since no incidental expense had been sanctioned by the Government to take care of such contingencies there was nothing that could be done, There wasn’t even money to pay for the team’s transport and practice sessions as the Organizers were firm about not Providing hospitality till a day be Sore the inauguration of the tournament.

It is no wonder then that Indian hockey teams, despite having talented players, cannot deliver anything more than an odd victory. And there will be no decisive recovering from mediocrity unless someone wakes up to the need to run hockey in a more professional manner. A more systematic and realistic interaction between the Indian Hockey Federation (IHF), the Sports Authority of India and the Sports Ministry is imperative.

The manager of the Indian team, Ghufrane Azam, spoke of exchange tours with European countries to improve standard of the game. Azam, who is also the vice-president of IHF and chairman of the selection committee, said, ‘We will go all out for the gold at Beijing.” India has no other choice. A failure to get the gold at Beijing could jeopardies India’s chances of even qualifying for the Barcelona Olympiad in 1992, forcing it to participate in the pre-Olympic tournament next year.

The countdown for Beijing begins now with a three week physical fitness camp at Lucknow to be followed by another five week camp at Bangalore. Besides the sweet taste of victory against two of the world’s top teams, the BMW outing has proved conclusively that the Indian hockey team has a kernel of talent around which a winning combination can be built with proper motivation, tactical planning and physical training.

Article extracted from this publication >> August 3, 1990