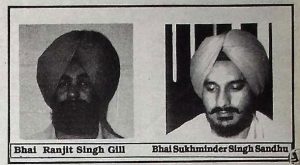

Sukhminder Singh Sandhu, a/k/a “Sukhi,” and Ranjit Singh Gill, a/k/a “Kukki,”

- Rargeting of the Respondents. The evidence submitted by the respondents is not limited to abuse of anonymous sikhs activists Rather, there is substantial proof that the respondents themselves would be in jeopardy if returned to India relatives and associates of the respondents have been subjected to physical and mental abuse in order to obtain information about the where about of Mr Sandhn and Mr_ (Chill. (Afft. T. AA CC). Mr. Gill himself was tortured while in police custody. (Aff. W). Furthermore the conduct of the Indian government during the extradition proceedings provides little assurance that the respondents would receive their judicial process. As noted above, Indian authorities failed to alert the United Stated Department of State that a linchpin of the criminal charges. The in criminating confession of Sukhdev Singh had been found untrustworthy More recently the Indian government has been dilatory in providing information about the disposition of criminal proceedings against others charred with the same offenses as the respondents.

The evidence sets this case a part from Ahmed V. Wager 726 F heat 389 (E. D.NY. 1989), aff’d 910 F. 2d 1063 (2d Cir. 1990). In Ahmad, the respondent presented to the district court proof that Israel had, at least in the past, subjected Arabs suspected of terrorism to inhumane treatment. Ahmad, 726 F. Supp. at 41617, But the court noted that “to suggest that certain practices may exist as to some prisoners…is not to prove that petitioner is likely to be subject to them.” Id. at 417. The court went on to find that Mr. Ahmad would not likely be abused because no person extradited by the United States to Israel had been denied due process, because he did not fit the profile of per sons abused by Israeli secret police, and because Israel had formally provided assurances that he would not be subjected to torture or other inhuman treatment. Id.

I cannot be so sanguine about the fate of the respondents here. The United States Department of State has apparently declined to seek any guarantees from the Indian government concerning the treatment of the respondents until after certifications of extraditability have been issued. Furthermore, the respondents squarely fit the “profile” of Sikhs subjected to abuse by Indian authorities. Indeed, they and those close to them have already been victimized. What may have been speculation in Ahmad has been shown to be reality here.

- Vitality of the Non Inquiry Doctrine

In light of the proffered evidence of systematic violation of the human rights of Sikhs by the Indian government and of the like hood that the respondents in particular would be subject to such abuses if extradited this is the rare case where judicial inquiry into the conditions in the requesting country would be warranted the government con cedes that the court has the capacity to conduct such an inquiry. It argues, however, that such an examination has been foreclosed by the Second Circuit. According to the government, Ahmad overrules any suggestion in Gallina of an exception to the non-inquiry doctrine. T reluctantly agree,

In Ahmad, the Second Circuit reviewed the evidence considered by the district court, including “testimony from both expert and fact witnesses and extensive reports, affidavits, and other documentation concerning Israel’s law enforcement procedures and its treatment of prisoners.” Ahmad, 910 F. 2d at 1067. The Second Circuit branded this inquiry “improper.” Id. It then reiterated the essence of then on inquiry doctrine: that a court may not examine conditions in the requesting country, and only the Department of State may deny extradition on humanitarian grounds, Id, This is the law of the Second Circuit, and must apply it. (In the aftermath of Ahmad, the language of the Gallina exception has been favorably cited by the Second Circuit only once in Saleh V. United state Department of justice, 962 F. 2d 234, 2Al (2d Cir. 1992). That was in the context of deportation, however, and there is no evidence that the Circuit views the non-inquiry doctrine as less than ab solute in extradition cases. See also Martin v. Warden, Atlanta Pen,, 993 F. 2d 824, 830 n.10 (11th Cir. 1993) (noting that in Ahmad, the Second Circuit “distanced itself” from Gallina).

Still, it is important to recognize the anomaly that is created. The Circuit’s strict adherence to the rule of non-inquiry in extradition cases is based on interests of international comity. See id.. Yet this circuit also recognizes that there is federal court jury is diction for cases in which one alien sues another for acts com mitted abroad that violate the law of nations. See Kadic V, Karadzic, 70 F. 3d 232, 238, 24346 (2d Cir. 1995) (federal court jurisdiction established by Alien Tort Claims Act,28 U.S.C. $ 1350, over violations of Torture Victim Protection Act of 1991, Pub. L. No. 102256, 106 Stat. 73 (1992)_codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1350 note and international law), cert, denied, U.S. ,116 S. Ct. 2524 (1996); Filartiga v. PenaIrala, 630 F. 2d 876, 880 (2d Cir. 1980) (just is diction under Alien Tort Claims Act for claims of torture by alien against foreign official). Thus, if the respondents were extradited and were subsequently tortured, they could then sue the responsible Indian officials in the United States. Inquiry into human rights abuses in the requesting country would only have been delayed, and the opportunity to prevent the abuse in the first place would have been lost. Nevertheless, this does not alter the fact that the Second Circuit now treats the non-inquiry doctrine as absolute.

Conclusion

The respondents argue that ex tradition’ to India will result in their “certain death.” Pin out such a definitive unfounded, there is Sufficient evidence to warrant a more searching inquiry into the possible fate of the respondents if they are extradited. However, an’ such inquiry is foreclosed by Ahmad. Accordingly, the motion to introduce evidence of human rights abuses and due process violations in India is denied. So Ordered.

James C. Francis IV

United States Magistrate Judge

Dated: New York, New York August 19, 1996.

Article extracted from this publication >> September 11, 1996