Kulwant Singh Mann remembers the 450mile train ride south from his home in the Punjab nine years ago. He also remembers the uncertain day and night he and his brother spent sleeping on the stone floor of a New Delhi church and how officials at the airport wouldn’t allow them out of the country with more than $15 in cash, After that, he recalls, he was too distracted by his jet airplane flight to notice details, too worried to keep up his diary. As the Indian countryside gave way to Tokyo, followed by the long jump over the Pacific Ocean, Kulwant’s journey dissolved into an endless blur of blue green water which he watched nervously through the plane window on his 12,000 mile flight to California.

Arriving in San Francisco ahead of schedule, Kulwant and his brother walked into one of the airport restaurants. Confident with his many years of English instruction, he told a waitress, “I need just wun glass vata.”

”Waddya mean, “vata,” asked the waitress. “Vata,” he said in his clearest English. She still didn’t understand him. It was at this point that Kulwant realized just how far away he was from his native India and how utterly unprepared he was for life in his new home.

On November 2, 1979, a date etched deep in his mind, Kulwant Singh Mann and his brother were met by his sister and brotherinlaw and driven to Mendota, in the Central Valley, a place hardly familiar with Kulwant’s religious sect, the Sikhs (pronounced “seek’’), yet home to 20,00030,000 of its followers.

After a month of working in the fields, Kulwant and his brother landed jobs in an alfalfa pellet plant. At night, they took English, auto mechanics, accounting and citizenship classes. When the alfalfa pellet plant job ended, they went for a drive and spotted a crew of farm workers. “We stopped and said “hello, amigo, have you got work?” recalls Kulwant. The Foreman said “yeah, come tomorrow. I asked, “Why tomorrow?” We want to work now.” Surprised, the Foreman agreed, and so Kulwant and his brother went to work on the spot.

When a labor dispute broke out at Jack Woolf Farms near Huron, Kulwant was employed as a crew chief, supervising 5060 Sikh replacement workers from Kerman and San Joaquin. Pleased by Kulwant’s work, Huron based labor contractor Ted Cruz hired him on permanent basis. As a result, Kulwant and his brother were able to repay their debts, bring their mother and father over from India, and move into an immaculate, three bedroom apartments in Huron.

By spring of 1984, Kulwant and his family had saved enough money to return to India, where he and his brother Harmail married two Punjabi Sikh women. Sixteen months later their wives finally obtained their entry visas and joined the family in Huron. After 1986, when a son was born to each brother, Kulwant’s mother began staying home to care for the children. Free to work in the fields, Kulwant, Harmail, their father and their wives now have accumulated enough money to begin thinking about purchasing a small pistachio or almond orchard or a raisin Vineyard.

The ancient home of the Sikhs lies halfway around the world from the Central Valley, in the fertile Punjab “land of five rivers” where India meets Pakistan, Tibet, and Nepal. The northwestern corner of this fertile plain, known as India’s breadbasket, funnels toward Afghanistan by way of the Khyber Pass, the ancient Mogul invasion route, site of innumerable battles and the key trade route on the road to Kabul. Sikhism began here in 1497, during a period of turmoil and domination by Afghan sultans, when Guru Nanak proclaimed the brotherhood of all people, particularly India’s outcast and downtrodden classes, irrespective of caste or race. Sikhs remained a peaceful, nonviolent sect until the 1960’s when two Sikh gurus were murdered by Indian emperors and Sikhs renounced nonviolence in favor of militant self-defense. Subsequently, all Sikhs took on the surname Singh or “Lion,” becoming famous as warriors for their fierce fighting.

Outside the Punjab, Sikhs account for only about 2 percent of India’s population which also. Includes Hindus, Moslems, Buddhists, Jains, Christians, and other religious groups. But inside the Punjab, Sikhs are slight majority in a largely rural society comprising thousands of small traditional villages. The spiritual center, Amritsar, a kind of Sikh Jerusalem located 15 miles from the Pakistani border, houses the Golden Temple, the Sikh’s holiest shrine.

No one is quite sure who first promoted the idea of abandoning the Punjab in favor of overseas immigration. Before coming to California around 1900, Sikhs had already gained a foothold in British Columbia, Canada, where they still remain an important part of the population. By 1920 there were about 7,000 Sikhs in California, most of them single men who had left their families behind and journeyed here with a father, brother, a cousin, or a friend from their home village. Working in Sacramento Valley rice and hop fields, Imperial Valley cotton farms (where they participated in the first cotton harvest in 1910), and southern California’s celery fields, they reorganized into gangs combined residential and work units directed by a group leader who marketed their labor on a contract basis.

“Before coming to California around 1900, Sikhs had already gained a foothold in British Columbia, Canada, where they still remain an important part of the population. By 1920 there were about 7,000 Sikhs in California.”’

Illiterate and largely unable to speak English, they did not assimilate, preferring to remain on the fringes of farm towns or on ranches, in a largely male society, where they ate, travelled, relaxed and worked together. Everything was shared, even the funeral and cremation expenses for any member who died, as well as a small sum to be sent back to his widow. Even though they were the lowest paid of all farm laborers averaging $1 $1.75 a day Sikhs managed to send half their income back to their families in the Punjab.

”I can only imagine how difficult it would have been,” says Gulzar Singh Johl, a Yuba City physician whose father came here at the turn of the century. “Almost all of them didn’t speak English and (the) Immigration (service) was on their tails. They faced just as much hardship as the original pioneers who came to this country. They just had to face different kinds of problems.”

Owing partly to the desire of many local farmers to break the Japanese monopoly on the labor supply at that time, Sikhs had little difficulty finding employment. Their success, however, caused resentment. Perceived as part of a Punjabi invasion, dubbed the “turbaned tide” and “ragheads.” Sikhs were described by the State Bureau of Labor Statistics as “‘the most undesirable immigrant in the state … unfit for association with American people.”

Small farmers, pressed by hard times, were particularly resentful of Sikhs, and supported largely unsuccessful lawsuits charging Sikhs with violations of anticline land laws.

Much like the Japanese, however, Sikhs graduated from wage labor for others to leasing farmland for themselves, despite the anticline land laws, which applied to Indians as well as Asians. There were many instances in which Sikhs pursued a dual employment pattern, common in India, where a group pooled resources to lease some land, while continuing to work on the land as laborers. The technique, which spread out risks, allowed Sikhs to plow profits back into acquiring more farms. As a result, by 1920, Sikhs had become important farmers in Glenn, Butte, Colusa, Sacramento, Sutter, Yuba and Imperial counties, where they leased 76,965 acres of land, most of it planted to cotton and rice. While the Japanese at the time had a ratio of 4.8 acres of leased land per person, the Sikhs averaged 33.5 acres, almost 7 times the ratio of the Japanese.

Sikh farmers remained active in the Imperial Valley well into the 1940’s (today no more than 30 Sikh farmers remain in the valley). But as pressures mounted to expand operations, mechanize and diversify, many Imperial Valley Sikh farmers found they were unable to operate according to traditional Punjabi arrangements. Migrating out of the valley, they settled in the Stockton area, where they constructed their first Sikh Temple. However, their numbers and influence continued to decline. By 1947, only 34 Sikhs owned about 1000 acres of farm land worth $185,775 most of it in orchards.

A historic event halfway around the globe in India was the primary reason for the resurgence of Sikh farming in California in the 1970’s and 1980’s. In 1947, following India’s independence from Great Britain, the country was split on religious grounds between the two predominant religious groups the Hindus and the Moslems. To avoid a civil war, the departing British simply divided India and Pakistan on paper hoping to separate Hindus from Moslems. The effects all over India and Pakistan, but especially in the Punjab, were disastrous. The Punjab, sacred homeland of the Sikhs, was divided between Hindu India and Moslem Pakistan. Reduced to about one third its originally size, the Punjab became the scene of massive violence, as Sikhs, Moslems and Hindus fought one another to retain territory and privileges of the past.

Before the repeal of restrictive immigration laws, thousands of Sikhs fleeing the civil strife in the Punjab came to California by crossing the border from Mexico as illegal aliens. Since 1965, when the Immigration and Nationality Act was amended and the limit on East Indians raised from 100 per year to 20,000, tens of thousands of Sikhs have migrated to America, with most settling in California’s Central Valley; 1020,000 in the Yuba City area, perhaps an equal number scattered between Fresno, Kerman, San Joaquin, Carthurs, Mendota, and Bakersfield. While many of those Sikhs still work as farm laborers or in farm related industries, a growing number have become contractors, foreman, farm tenants, and farm owners. Sikhs now prow 60 percent of the California cling peach crop and half of all the states prunes. They also raise almonds, walnuts, kiwifruit, feijoas, rice and raisins.

Like many of the most successful Sikh farmers, Bains is part of the third generation, an educated grandson of an original Sikh settler. His grandfather, Kartar Singh Bains was the first of the Bains family to come to California in the early 1900’s although he never had much financial success. Grandson Didar Singh Bains was a farmer in the Punjabi village of Nangal Kurd. But when overcrowding and conflicts with the Hindu controlled irrigation officials developed 30 years ago, Bains followed his grandfather and father to California.

In 1964 he married the daughter of one of the most successful Sikh nurserymen. The capital from that union, plus his family money, plus the money Didar earned, allowed him to expand his Yuba City base. By 1974 he had a gross income of $2 million. Today he farms $10,000$15,000 acres of crops scattered from British Columbia to Bakersfield.

One key to Didar Bains’s success, besides his family backing and his own abilities, is his wife Senti. Like most Sikh marriages, Senti’s union with Didar is not just a personal union; it represents the close coupling to two families into an economic unit. Senti is anything but a passive observer of the family business.

With her husband frequently on the road supervising his far-flung farming empire. Senti handles the day to day farming decisions, ranging from hiring farm laborers and supervising harvest operations to filling out W2 forms and preparing tax schedules and payments. Her work continues until well after dark, when she finishes preparing payroll checks, returns home, and prepares dinner. Then she speaks with a foreman about the next day’s work. Late that night she speaks by telephone with Didar, who is in British Columbia. He gives Senti a picking schedule and target dates for finishing the harvest of each peach variety. Senti then calls her foreman. She wants to stay on schedule and make contingency plans to use machines if a labor shortage develops and picking falls behind.

Yet the Bains have not forgotten their Sikh values. They have become the most important sponsors of Sikh immigrants. Since 1975, about 150 members of the Bains family, including Didar’s two brothers and five sisters and all their relatives, have immigrated to California under Didar’s sponsorship. And most of them, at one time or another, have found jobs somewhere in Didar Bain are farming operations.

But many Sikhs in California agriculture remain laborers one step removed from farm ownership, like Kulwant Singh Mann, Living in an apartment with his mother, father, brother, wife, sister-in-law and four young sons, he looks to the future. On Sunday’s he drives to his temple in San Joaquin, taking food and beverages for the communal kitchen, while also contributing up to 10 percent of his income to the church, He also supports an independent Sikh state in Punjab and follows events in India closely.

His eyes red from a day under the sun yanking nightshades out of San Joaquin Valley cotton fields, Kulwant is clearly tired as he relaxes late one evening. At 4 a.m. he had risen with his brother to collect 60 Sikhs from San Joaquin and Kerman and then deploy them in several fields, he had cashed a check from his employer and prepared the payroll for his crew.

Kulwant is on his way to becoming a farmer. He is already an entrepreneur and an independent businessman, 12,000 miles from the Sikh villages of the Punjab. He does this for his family, for the future, and for the Sikh sect, it has been a struggle, but Kulwant is debt free and he has been able to help others come from the Punjab and adjust to America. And yet he worries.

”I see more and more of the younger generation trying to get jobs in the cities,” he says. “They don’t seem to be that interested in farming. Too much hard work, too much spray and dust. It’s mostly the old-timers who remember the Punjab, who wear the turbans and follow the old ways, and who like being farmers. Maybe 10 years from now there won’t be any new Sikh farmers.”

In another room, his brother and sister-in-law rise and dress for the night shift at a pistachio packing plant. When his brother appears, he is wearing Levi’s and a baseball cap. His sister-in-law is in designer jeans and a plaid shirt.

“When we left the Punjab we were pure Sikhs,” Kulwantsighs. “But now, whenever we go back, we will be Americans.” On December 12, 1988, Kulwant and his wife Nimmi Mann became U.s. citizens, another step in their long journey to their new chosen home.

“Sikhs now grow 60 percent of the California cling peach crop and half of all the states prunes.

Sikhs cite two reasons for cultivating canning peaches. Ones the small scale of operation required for adequate profits. On a simple ratio of yield times priceperton times acreage, only strawberries require less land than cling peaches. The other reason was the very high labor costs required to bring an acre of peaches to the cannery. In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, thinning, pruning, and picking accounted for over half the expenses. By doing the bulk of all thinning and pruning operations themselves and by living modestly on the farms and holding down personal expenses, Sikh peach growers were able to survive in an industry so severely depressed that it required massive orchard clearings in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s.

A lot of the big farmers would just drive by and rely on managers,” says Cling Peach Advisory Board member Gian Singh Johl. “They didn’t live in the orchards. But Sikhs were there all day in the fields themselves. They knew what was needed. And they were able to get quality and quantity where others couldn’t.

Sikh success in peach growing and other orchard work in and around Yuba City became the basis for the reconstruction of Sikh society in the Central Valley. Successful farmers immediately sponsored immigration of family members, and if possible, old friends from the Punjabi village.

“We don’t believe in welfare,” says Ajayab Dhaddey, a field representative for the Cling Peach Association. “We always provide work for people when they come cover here. Some Sikh farmers’ might just have a family come in and tend and thin the crop in exchange for a small house and some money. On the larger ranches, where more labor is needed a Sikh farmer might hire a dozen or more families. (In 1987) when others were having a labor shortage, we didn’t have many problems because of all the Sikhs who were willing to work.”

Taught to shun pride in high birth or shame in low birth, and to regard all tasks as noble and worthy, Sikhs ensure their success through plain hard work.

“Sikhs don’t mind going from 6 a.m. to 9 p.m.” says David Rai, a Sikh rice farmer in Yuba City. “They’ll have dinner at 10 p.m. at night at harvest time if it is necessary.

Besides hard work, Sikh farmer families demonstrate two additional characteristics. One is willingness to pool resources for the common good, thus ensuring that even if each individual is earning a minimum farm worker’s wage, a Sikh extended family of 68 people collectively lives well.

The second characteristic of Sikh farm families is extreme frugality, coupled with intelligent use of money “We don’t buy our groceries in Huron because it’s so expensive there,” explains Huron based Harmail Singh Mann,

“Everything is much cheaper in Kerman and Coalinga.”

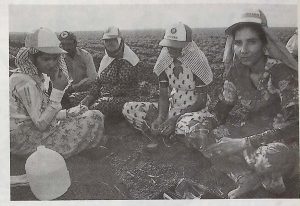

Traditional Sikh men were brightly colored turbans with uncut hair twisted beneath, while the women are fond of sashes loosely wound around the waist and partial veils.

“The Sikh people are trying to preserve their heritage,” says G’S. Gill. “A lot of them have a hard time adapting to life in the valley.”

Sitting in the home of Didar Singh Bains, the largest Sikh farmer in California and the most famous leader of Yuba City’s Sikh community, an outsider might think Gill is wrong. Bains, who farms peaches, raisins, prunes, raspberries, alfalfa, almonds, cotton, corn, cantaloupes and cranberries, looks very much like a man of two worlds in his black turban, long beard and brown pinstriped business suit. There’s a new Mercedes parked outside, and inside are numerous mementos from Bains’s service on the state Board of Agriculture and his term as President of the World Sikh Organization.

Yet even for Didar Bains, one of the many Sikhs who obtained a high school education and proficiency in English before immigrating, the adjustment to California was difficult. “The first few years I shaved my beard,” he says, “I didn’t even wear my turban until 1980. Then I decided I can’t forget my home and religion. So now I wear my turban and beard. But I do not dream in English. Dream in Punjabi. Sometime I wake up dreaming about the villages of home. I say “Oh Didar, you are in California, not Punjab.

But what has been difficult for Didar Bains has been impossible for many other Sikhs. While the Sikhs experience in California agriculture appears to be a tribute to human perseverance and the power of religion and family, it also has its downside: fragmentation of old values, ostracism, and discrimination. Life is especially hard for illegal Sikhs.

*I¢’s a disappointment for them,” says Jayat Raye, an official with the West Sacramento Sikh Temple, who occasionally serves as an interpreter for illegal Sikhs arrested by the Border Patrol. “They never expected this. They came here thinking the money is like leaves on a tree. They wind up sleeping where the farmers park tractors. Their lives are miserable. They come to our temple because we have a free lunch and they can find someone to talk with them and help them.”

Although Sikhs have started to diversify into teaching, independent businesses, and trucking, it was the hope of farming that attracted the Sikhs to the Central Valley, and it has been in farming that they have experienced the full spectrum of triumphs and disappointments. Of the 20, 00030,000 Sikhs in the Sacramento and San Joaquin valleys, perhaps 2,000 own or operate farms. Most work as farm laborers, usually in family units, thinning and picking peaches, supplementing that with winter pruning and harvest work in other crops.

*We arrived here single and with ambitions,” says Gian S. Johl, one of the most successful Sikh farmers in Yuba City, “We all think, if we can just buy a little farm we can be like we were in Punjab. But when wearer here a while, we see it is not so easy.”

In the Punjab, the Sikhs were familiar with many modern irrigation and fertilization practices. In America, however, they found agriculture was even more intensively pursued. “In India we don’t grow grapes in long rows like here. We grow them like trees, on a square screen to save the land,” says Kulwant Singh Mann. “When I first see grapes here I ask, “What is this?” That’s when I realize I have a lot to learn.”

One of the most successful Sikh farmers is Didar Singh Bains. Bains came to California in 1958, settling in Yuba City where he went to work as a manager for an Italian farmer. “In 1962 I bought 26 acres of overland just down the road,” he recalls. “I lived frugally, supervised all the work myself. After a couple of years I had enough money to plant the 26 acres to peaches. That was the beginning.

This article was published in the California Farmer. It has been reprinted with permission.

Article extracted from this publication >> February 10, 1989