A Struggle for Human Dignity in the Indian Subcontinent

by Pieter Friedrich and Bhajan Singh

“You must take the stand that Buddha took. You must take the stand which Guru Nanak took. You must not only discard the Shastras, you must deny their authority, as did Buddha and Nanak. You must have courage to tell the Hindus that what is wrong with them is their religion — the religion which has produced in them this notion of the sacredness of caste.”

— Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar —

California, USA

Published 2017 by Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc.

Captivating the Simple-Hearted: A Struggle for Human Dignity in the Indian Subcontinent

Copyright © 2017 by Pieter Friedrich and Bhajan Singh. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopied, recorded, or otherwise) or conveyed via the internet or a web- site without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical books, articles, or reviews.

Front cover features Sikh students in Uttar Pradesh. They belong to a com- munity commonly called “Sikligar Sikhs” who originated from a Mulnivasi group who manufactured weapons for the Sikh Gurus, beginning with Guru Hargobind. The back cover features Harmandir Sahib in a simpler time.

Inquiries should be addressed to:

Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc.

California, USA

wwww.SovStar.com

ISBN 978-0-9814992-9-1; 0-9814992-9-5

— TABLE OF CONTENTS —

Foreword by Dr. V. Rajunayak

Prologue

1. Mulnivasi Flock to the Warm Shop

2. Guru Arjun Carries the Caravan Forward

3. The Simple-Hearted: Progressing From “Worms” to Free People

4. Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s Sikh Empire

5. Dr. Ambedkar’s Warning: “There is Great Danger of Things Going Wrong”

6. Independent India: Bleeding the Sons and Daughters of the Soil

7. Swaraj Without Azadi

Epilogue

Glossary Bibliography

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Foreword

by Dr. Vislavath Rajunayak

Histories about India have been written and re-written. Many Indian historical narratives are written from a dominant perspective to justify Brahmanical Hindutva ideology. The facts have been completely removed from history.

Authoritarian forces antagonize the history of marginalized communities as well as the struggle of “other” Mulnivasi martyrs. Captivating the Simple-Hearted challenges historians who appropriate merely ideological interpretations to write histories of the marginalized people of the Indian subcontinent. The authors demonstrate that one can see history through Mulnivasi eyes.

In order to fully understand the community, a detailed study of the Sikh history needs to be read. It has been provided in this book. Captivating narrates both individual and community historical accounts with accurate dates and contemporary references. Moreover, it opens up a new area of scholarly inquiry that has been pushed underground to conform to the hegemony of the prevailing narratives.

Captivating is an eye-opener for any reader to understand the dynamic and humanitarian approach and vision of the Sikh Gurus towards the Mulnivasi in India. The authors reveal the historical and systematic processes which tried to thwart that vision. They bring to light the dominant and exploitative role played by an alliance of Mughal nobles and Brahman elites to suppress the desires of Mulnivasi people to claim their humanity. The authors underline the need to reexamine history to authentically understand the struggles of marginalized communities.

The authors bring to life proper histories in a technical sense; nevertheless, the histories are not simply imaginative negotiations with the past but are also relevant to contemporary conditions of life and identity.

Captivating the Simple-Hearted

Even today, histories of these marginalized communities are not accessible to their members. Due to this ambiguous relationship with historical narratives, we can say that this book enlightens the Mulnivasi on their past by giving accurate, contemporary references and disproving dominant historical narratives. I am sure this book will help readers to reclaim their own identity.

A quick examination of this literature creates an immense pride in the Sikh Gurus. If you read Captivating the Simple-Hearted, you will be amazed to know about the Gurus’ wonderful proclivity towards the Mulnivasi. Anyone who wants freedom in this world should partake of this history to learn about facing today’s challenges.

Dr. Vislavath Rajunayak is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Indian and World Literatures at the The English And Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad and a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for South Asian Studies at University of California, Berkeley

Prologue

“India needs such a history that germinates revolutionary consciousness for social change because history plays a very significant role in this respect,” writes Indian advocate Dr. Santokh Lal Virdi. “Society assumes a character and shape as molded by its history.”1

From before the point of recorded history, the issue of caste — that is, the hereditary and hierarchical division of humanity — has been at the epicenter of sociopolitical conflict in South Asia. Therefore, South Asian struggles for equality and liberty (or, in short, human dignity) can be best understood in context of resistance to the caste system. Within that paradigm, the Sikh Revolution is central to the struggle for emancipation of those enslaved by caste.

Within that context, Dr. Rajkumar Hans (an Indian intellectual who was considered a Dalit or “Untouchable” by virtue of his ancestry) summarizes the significance of the rise of the Sikhs.

Growing out of the powerful, anticaste sant tradition of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in northern India, the Sikh variant of Guru Nanak and his successors evolved into an organized religious movement in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It became a rallying cry for the Untouchables and members of the “lower castes” that they be allowed a respectable social existence….

Guru Nanak felt that the real cause of the misery of the people was the disunity born of caste prejudices. To do away with caste differences and discords, he laid the foundation of sangat (congregation) and pangat (collective dining). Thus, all ten of the gurus took necessary steps to eliminate the differences of varna and caste.2

This book shows how the Sikh Revolution developed with the specific

intent of eliminating the social divisions of caste, instilling the masses with

Captivating the Simple-Hearted

a sense of the universal nobility of the common person, and empowering the people to defy and prevail against sociopolitical tyranny.

Offering a survey of many critical points of the history of the Indian subcontinent from the 5th century to the 21st century, we present the struggle for liberation as the principal theme. Captivating the Simple-Hearted details the eradication of Buddhism in the 500s to 900s, the emergence of Bhagats (saints) in the 1200s to 1500s, the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in the 1200s and of the Mughal Empire in the 1500s, and the development of the Sikh philosophy from the 1500s to 1700s. Our narrative reveals the unbroken thread connecting all of these historical developments.

Along the way, we examine the origins and impact of Brahmanism (the underlying philosophy of the Hindu religion), the alliance between Brahmans and Mughals, the lives and teachings of several of the Sikh Gurus, the schemes perpetrated against the lives of the Gurus by a Mughal- Brahman alliance, the martyrdom of three Gurus, the wars waged against the Mughal Empire and the Hindu Rajas by the Sikhs, the spread of the Sikh philosophy across the Indian subcontinent, the independence of Punjab, the rise and fall of the Sikh Empire, the occupation of the subcontinent by the British Empire, the emergence of social reformers in the 1800s, the interactions between Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar and Mohandas Gandhi as the Indian subcontinent pursued independence from British rule, and the impact of these historical realities on the present conditions of the Republic of India.

“There is no work on Sikh history and tradition that has been produced from the Dalit history perspective,” wrote Dr. Hans.3 Thus, we hope that Captivating the Simple-Hearted will clearly demonstrate (especially as we rely on objective Persian and European primary sources for evidence) that Sikhism, at its core, seeks alliance with those considered “low born.” This history brings to light how the Sikh Panth (path) sought — and secured — liberation of the subjugated masses.

Bhai Jaita (c. 1649-1704), a poet and a warrior in service of Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth Sikh Guru, exemplified the fulfillment of that goal. Jaita was born as a Dalit. Yet, according to Dr. Hans, “Jaita emerged as a fearless Sikh warrior who so endeared himself to the tenth guru that he was proclaimed by the guru as the panjwan sahibjada (fifth son) in addition to the guru’s own four sons.” Renamed by the Guru as “Baba Jiwan Singh,” he was “killed in a fierce battle with Mughal armies in 1704.”4 His legacy lives on, however, in his poetry. In one of his verses, a rahit (code) for the Sikhs,

Friedrich & Singh

Baba Jiwan Singh declares,

Now listen to the rahit of the Singhs.

The Singh should pray to God, keeping war in mind. When a victim and a needy person beseeches help,

Forgetting his own, a Singh should remove others’ suffering. Not keeping in mind differences of high and low caste,

The Singh should consider all humans as children of God. Abandoning the Brahmanical rituals and customs,

The Singh should seek liberation by following the Guru’s ideas.5

Ideas have consequences. The ideology of Brahmanism has deadly consequences, but the contrasting idea of Sikhism restores life to a desolate land. Beliefs influence behavior. The beliefs of Brahmanism produced a society of inequality and tyranny, but the contrasting beliefs of Sikhism inspired a devotion to the universal equality and right to liberty of all humanity.

Today, Sikhism has not only taken root in South Asia but spread across the globe. However, its rival of Brahmanism has yet to be fully uprooted. Indeed, it remains a predominant, coercive, and treacherous force in modern India and threatens to spread. From its origins as an ancient prejudice, Brahmanism has evolved into a politicized form of violent nationalism which is menacing to every citizen of the Republic of India who wants a free and peaceful society.

We hope that examining one of the Indian subcontinent’s central struggles for human dignity will expose the impact of historical realities on current events. To transform our future, we must first comprehend our past.

Citations

1 Rawat, S. Ramnarayan and K. Satyanarayana (eds.). Dalit Studies. Durham: Duke University Press. 2016. 136.

2 Ibid., 131 & 134.

3 Ibid., 136.

4 Ibid., 137.

5 Ibid., 135-136.

— 1 —

Mulnivasi Flock to the Warm Shop

The martyrdom of Guru Arjun (1563-1606), carried out in Lahore under the orders of Delhi Emperor Jahangir (1569-1627), was a turning point in the struggle of the people of the Indian subcontinent to secure their human dig- nity. This struggle was compounded by foreign invasions which imposed a dehumanizing sociopolitical structure.

Guru Arjun’s persecution was instigated by the elite who benefited from the centuries of oppression produced by the caste system, a power structure which enslaved South Asia’s indigenous people. The diverse indigenous communities, ranging from Punjab to Nagaland and Kashmir to the Tamil country, included Adivasis (tribal peoples), Shudras (the lowest of the four castes), and Ati-Shudras (outcastes). United by their exclusion from society, which is dictated by the caste system, these communities represent the ma- jority of the population. In company with others who fundamentally reject caste and its hierarchical system of repression, they are collectively known as the Mulnivasi Bahujan (original people in the majority).

From 20th century civil rights champions like Dr. Bhim Rao Ambed- kar, the Mulnivasi (original people) can trace their fight for equality and liberty back to South Asian Gurus (spiritual teachers) like Arjun, Nanak, Ravidas, Kabir, Namdev, Farid, and other torchbearers in the struggle to secure the human dignity of the common person.

Occurring at the height of Guru Arjun’s endeavor to institutionalize that struggle as the Sikh Panth, his arrest, torture, and execution was a landmark attempt by Brahmans (the high-caste elite), in collaboration with Mughal invaders, to suppress a flourishing movement to secure the liberation of the downtrodden Mulnivasi.

The Warm Shop — In his memoirs, Jahangir (whose great-grandfa- ther, Babur, established the Mughal Empire’s foreign rule of India) clearly details his reasons for persecuting the Guru.

There lived a Hindu named Arjun in the garb of Pir [saint] and Sheikh [king], so much so that, having captivated many sim- ple-hearted Hindus — nay, even foolish and stupid Muslims — by his ways and manners, he had noised himself about as a religious and worldly leader. They called him Guru, and from all directions fools and fool-worshippers were attracted towards him and ex- pressed full faith in him. For three or four generations, they had kept this shop warm. For years, the thought had been presenting itself to me that either I should put an end to this false traffic or he should be brought into the fold of Islam….

When this came to the ears of our majesty, and I fully knew his heresies, I ordered that he should be brought into my presence, and having handed over his houses, dwelling places, and children… and having confiscated his property, I ordered that he should be put to death with tortures.1

This historical account produces an ocean of questions. Who was Ar- jun? Who were the simple-hearted? What heresies was Arjun accused of teaching? If Jahangir saw simple-hearted, did he also see complex-hearted? If the simple-hearted were swayed by Arjun’s “ways and manners,” why were the complex-hearted not swayed? How did Jahangir believe Arjun captivated the hearts of the simple? Who lost if the hearts of the simple remained captivated? Who won if the simple-hearted lost their attraction to the Guru’s message? Indeed, who were the simple-hearted — and who were the foolish and stupid?

Answers are found in the origins of the “warm shop” of “three or four generations” which disturbed Jahangir — so deeply did it disturb him, in fact, that he even describes members of his own Islamic religion who were attracted to Arjun as “foolish and stupid.”

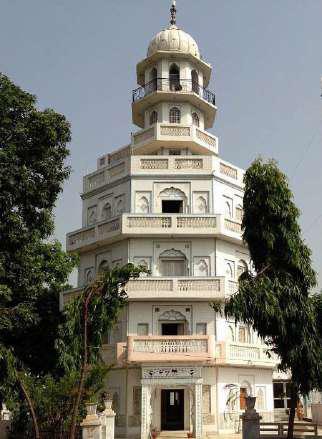

In 1604, under the auspices of Guru Arjun, this warm shop took phys- ical form in completion in Amritsar, Punjab of the simple structure of Har- mandir Sahib (later known as the Golden Temple), an institution whose four doors brought fresh air to the lungs of the suffocated Mulnivasi.

The Gurdwara (God’s doorway) was open to all and designed to em- power the common people to embrace their intrinsic self-worth. From this focal point in Amritsar, the Sikh (a lifelong “disciple” or “student”) com- munity carried out its work of liberating the masses by preaching equality, educating the ignorant, and practicing langar — a free kitchen that defied

caste taboos by providing people with a place to sit together, touch each other, and break barriers by eating and drinking with one another regardless of social status.

At this warm shop, the Shudras and Ati-Shudras, previously indoctri- nated by the prevailing Brahmanical culture to be terrified of their own shadows, were shown how to love themselves and their neighbors. They discovered new life in the uranium of everlasting energy flowing from the Adi Granth, the collected teachings of South Asian saints who proclaimed the human dignity of all people. The spines of these enslaved masses, bro- ken from being forced to bow and scrape before Brahmans and Emperors, found relief in voluntary surrender to the ideas of liberty contained within the Granth.

Once victims of a power structure that enslaved them, those mocked by their oppressors as “simple-hearted,” “foolish,” and “stupid” were ines- capably captivated by a message that offered liberation. As these sons and daughters of the soil lived out the teachings of the Granth, Harmandir Sahib produced a monsoon to water the hopes of the hopeless while simultaneous- ly flooding the strongholds of their oppressors. The ruling elite were under- standably terrified by this flourishing institution — or “shop” — which was so heavily patronized by free people.

This shop, which Jahangir said was kept warm “for three to four gen- erations,” was opened by the first Sikh Guru, Nanak (1469-1539), who de- clared, “There is neither Hindu nor Muslim, so whose path shall I follow? I shall follow God’s path.”2 As he began following that path, traffic trickled after him. It was a path less travelled and entirely unfamiliar to the com- plex-hearted because, as Guru Nanak explains, God’s path requires inten- tional association with the downtrodden,

ਨੀਚਾ ਅੰਦਿਰ ਨੀਚ ਜਾਿਤ ਨੀਚੀ ਹੂ ਅਿਤ ਨੀਚੁ ॥

ਨਾਨਕੁ ਿਤਨ ਕੈ ਸੰਿਗ ਸਾਿਥ ਵਿਡਆ ਿਸਉ ਿਕਆ ਰੀਸ ॥

ਿਜਥੈ ਨੀਚ ਸਮਾਲੀਅਿਨ ਿਤਥੈ ਨਦਿਰ ਤੇਰੀ ਬਖਸੀਸ ॥

The lowliest of the lowly, the lowest of the low born,

Nanak seeks their company. The friendship of great is in vain. For, where the weak are cared for, there Thy Mercy rains.3

Guru Nanak’s friendship with the “low born” signified a declaration

of war against the Indian subcontinent’s reigning power structure. Accord-

ing to the elites, only those born at the top of the culture’s caste system had access to God; those at the bottom were not even considered human. Yet the Guru preached the equality of everyone, saying, “Recognize the Lord’s Light within all, and do not consider social class or status; there are no classes or castes in the world hereafter.”4

Those who stopped considering caste, the Guru suggested, gained emancipation. As he says, “That slave, whom God has released from the restrictions of social status, who can now hold him in bondage?”5 Caste, he explained, is irrelevant to a person’s natural right to liberty because all are equal before the Creator. Everyone, no matter his or her origins, obtains liberty through the same method. As he stated, “The Brahmans, the Ksha- triyas, the Vaishyas, the Shudras, and even the low wretches are all emanci- pated by contemplating their Lord.”6

Laying the foundation for a recurring doctrine of the Panth, Guru Nanak emphasized the irrelevance of royal birth. “Even kings and emperors with mountains of property and oceans of wealth cannot compare with an ant filled with the love of God,” he declared.7 The concept that the lowest creatures can be superior to those born as royalty was embraced and ex- panded by his successors, especially Guru Arjun (who taught that paupers can become princes). Furthermore, Guru Nanak explains,

ਖਖੈ ਖੁੰਦਕਾਰੁ ਸਾਹ ਆਲਮੁ ਕਿਰ ਖਰੀਿਦ ਿਜਿਨ ਖਰਚੁ ਦੀਆ ॥ ਬੰਧਿਨ ਜਾ ਕੈ ਸਭੁ ਜਗੁ ਬਾਿਧਆ ਅਵਰੀ ਕਾ ਨਹੀ ਹੁਕਮੁ ਪਇਆ ॥

The Creator is the King of the world; He enslaves by giving nourishment.

By His Binding, all the world is bound; No other Command prevails.8

The battle lines were thus clearly drawn between society’s Touchables and Untouchables — between those who sought to command others and those who understood they do not have to answer to the command of any- one except the Creator.

Guru Nanak developed this message by weaving together the threads of liberty spun by preceding saints. Traveling throughout the world, he be- came the Steward of the Mulnivasi by knitting together into a single fabric the records of resistance and celebrations of human dignity of others who similarly pursued emancipation of the oppressed. As the originator of the

Panth, it was left to him to institutionalize the message of social, econom- ic, and spiritual freedom proclaimed by the saintly Bhagats who preceded him.9

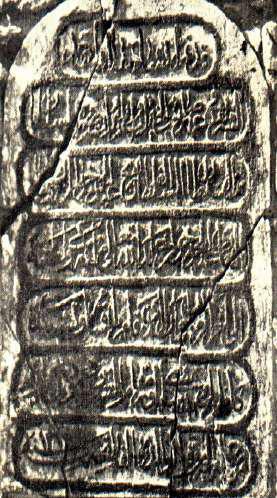

One of the earliest of these Bhagats was Baba Farid (1179-1266), a poet whose compositions formed the foundation for the Punjabi language.

Brahmanism Cripples India — Farid lived in a transformative era for the Mulnivasi as historical events found them torn between two vicious forces. On one side were Islamic invaders who, during Farid’s lifetime, achieved a conquest of Delhi that lasted until the 19th-century. On the other side were Brahmans who imposed and brutally enforced the intense seg- regation of the Hindu caste system. Detailing the significance of the caste system, German sociologist Max Weber writes,

Caste, that is, the ritual rights and duties it gives and imposes, and the position of the Brahmans, is the fundamental institution of Hin- duism. Before everything else, without caste, there is no Hindu…. “Caste” is, and remains essentially, social rank, and the central po- sition of the Brahmans in Hinduism rests primarily upon the fact that social rank is determined with reference to Brahmans.10

Because caste hierarchy ranks a person’s social status in “reference to Brahmans,” the practice is also known as “Brahmanism.” One of the most penetrating analyses of Brahmanism was written in the 20th century by a Hindu named Swami Dharma Theertha. An attorney from Kerala who gave up his practice to become a monk, he devoted his life to teaching against caste. In 1941, after decades of studying the Hindu religion, he published a book entitled History of Hindu Imperialism. Subsequently, he renounced Hinduism entirely.

Referring to Brahmans, Theertha writes, “So far as the Hindus are con- cerned, all power has remained for many centuries in the hands of a small group of hereditary exploiters whose life and interests are even today antag- onistic to the welfare of the masses of India.”11 In History of Hindu Imperi- alism, he defines Brahmanism.

Brahmanism is the name used by historians to denote the exploit- ers and their civilization. It may be defined as a system of sociore- ligious domination and exploitation of the Hindus based on caste, priestcraft, and false philosophy — caste representing the scheme

of domination, priestcraft the means of exploitation, and false phi- losophy a justification of both caste and priestcraft. Started by the Brahman priests and developed by them through many centuries of varying fortunes and compromises with numerous ramifica- tions, it has, under foreign rule, become the general culture of the Hindus and is, at the present day, almost identical with organised Hinduism….

Its strength depends on an ingenious organization of society in which the hereditary priest is supreme, priestcraft is the high- est religion, and philosophy is the handmaid of priestcraft. Origi- nally, the scheme contemplated only four caste divisions, but the process of classification by birth and social exclusiveness, once brought into fashion, gave rise to many thousands of castes and sub-castes.12

In the 12th century, at the time of Farid, Buddhism was South Asia’s only indigenous religion which suggested temporal equality. Approximate- ly 1700 years before Farid, Gautama Buddha traveled and taught through- out eastern parts of the subcontinent; his philosophy took deep root and flourished for a time.

Describing Buddhism’s impact on a caste-ridden society, Theertha writes, “Wherever the Buddha’s teachings spread, they created a revolution in the mentality of the people. Liberated from the artificial restrictions of caste, they delighted to mingle their thoughts, activities, and destinies in the free flow of human friendships, attachments, and love, and many Brahmans even broke through their orthodoxy to share in this new freedom.”13

Ultimately, however, the free expression of liberated human beings was intolerable to those who benefited from censoring it. As Sikh historian Dr. Sangat Singh reveals, “Gautama Buddha, like the Sikh Gurus, earned the deep-rooted hostility of Brahmanism because of his revolt against the Brah- manical caste system, priestcraft, and rituals.” Consequently, the Buddhists were mercilessly, brutally, and almost completely driven out of South Asia. From the 5th century onwards, Dr. Singh describes an “ongoing… attack on the Buddhists and their places of worship.” Frequently, the Brahmans were “cooperating with foreign invaders like Huns and early Kushans to strike at the roots of Buddhist power.” Ancient Buddhist cities were eradicated; “Kapilvastu [in Nepal] had become a jungle and Gaya [in Bihar] had been laid waste and desolate.” In Bengal, King Shashanka “carried out acts of

vandalism against the Buddhists, destroyed the footprints of Lord Buddha at Pataliputra [in Bihar], burnt the Bodhi tree under which he had meditated, and devastated numerous monasteries, and scattered their monks.”14

Facing constant persecution, thousands of Buddhist monks fled the In- dian subcontinent. “All of them and others who followed later to China, Tibet, or to Korea and Japan, were fugitives from oppressive Brahmanism, which threatened their very existence.” Subsequently, in the 9th century, philosopher Adi Shankaracharya oversaw “an all-out Brahmanical assault on Buddhism.” Dr. Singh explains,

Shankaracharya himself killed hundreds of Buddhists of Nagarju- nakonda [in Andhra Pradesh] and… “wantonly smashed” the Bud- dhist temples there…. Shankaracharya, thereafter, led the group of marauders to Mahabodhi temple in Gaya, and they indulged in large-scale destruction of Buddhist monasteries and stupas. The Brahmans took over the temple under their control.

His appetite whetted, Shankaracharya personally led a mo- tivated group through the Himalayas. The object now was the Buddhist centre at Badrinath [in Uttarakhand]. His reputation of wholesale destruction of Buddhists preceded him. The Buddhists chose to abandon Badrinath. They threw the statue of the presiding deity in Alakananda river at the foot of the temple and escaped to Tibet. The centre was taken over by the Brahmans.15

Thereafter, Muslim occupation — which took root in the heart of the subcontinent with the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206 — cre- ated ideal conditions for Brahmans to expand the slavery of the caste sys- tem. “It was only when the country ultimately fell a victim into the hands of foreigners that Buddhism was crushed to death and Brahmanism spread its fangs over the prostrate people,” explains Theertha. “Brahmans favored the religion of gods and goddesses and rituals, and not the religion of righ- teousness.”16

While foreign occupation enabled Brahmanism to finally eradicate Buddhism, it was Brahmanism itself that enabled foreign occupation to take root. Muslim warlords invaded the Indian subcontinent from the northwest by passing through Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Punjab. In 711, Muhammad bin Qasim (born in Arabia) secured the earliest successful Islamic foothold in the subcontinent when he conquered Sindh and part of Punjab (areas now

in eastern Pakistan). “Many causes contributed to the subjugation of Sindh,” writes Indian historian Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava. Chief among those causes, he explains, were caste divisions.

The province was internally disunited and unable to resist a mighty invader like the Arabs. Its population was sparse and heterogene- ous.… The lower orders of the society were badly treated. The Jats, the Meds, and certain other castes were looked down upon and subjected to humiliation by the ruler, the court, and the offi- cial class no less than by the higher caste people. They were not allowed to ride on saddled horses, to carry arms, or to put on fine clothes. Owing to these circumstances, social solidarity, the best guarantee of political independence, was conspicuously lacking.17

Qasim’s conquest enabled further inroads by other Islamic warlords, which continued for several centuries until, finally, Turkic warlord Qutb al-Din Aibak (1150-1210) established the Delhi Sultanate in 1206. In 1526, Ibrahim Lodi became the last ruler of the Delhi Sultanate when he was killed in battle by Uzbek warlord Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad (1483-1530)

— commonly known as “Babur,” meaning “tiger” — who established the Mughal Empire.

From 1206 to 1947, the majority of the Indian subcontinent largely remained under uninterrupted foreign rule.

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier, a 17th-century French merchant who wrote about his travels in the Mughal Empire, corroborated Srivastava’s 20th-cen- tury conclusion that the caste system enabled India’s subjugation by foreign invaders. “The idolaters of India are so numerous that for one Muhammad- an there are five or six Gentiles,” writes Tavernier. Nevertheless, their nu- merical superiority did not empower them to resist invasion. He continues,

It is astonishing to see how this enormous multitude of men has allowed itself to be subjected by so small a number of persons, and has bent readily under the yoke of the Muhammadan princes. But the astonishment ceases when one considers that these idol- aters have no union among themselves, and that superstition has introduced so strange a diversity of opinions and customs that they never agree with one another. An idolater will not eat bread nor drink water in a house belonging to any one of a different caste

from his own.18

Foreign occupation was irresistible by a society divided into castes. Even then, however, the occupation might have inspired the common peo- ple to jettison caste and unite in resistance to the invaders. Yet this was prevented by the high-caste — the Brahmans — who ingratiated themselves with the conquerors, secured privileged positions in the courts of the foreign Emperors, and used the occupation as an opportunity to entrench Brahman- ism. According to Theertha, the caste system took deeper root as Brahmans collaborated with the occupiers.

The disappearance of Buddhism and the passing of political power into the hands of Muhammadans, though they meant the extermi- nation of national life, was a still triumph for Brahmanism…. One prominent result of the invasion of India by the Muhammadans was that, so far as Hindu society was concerned, Brahmans be- came its undisputed leaders and law-givers…. When the Muham- madans had overcome all opposition and settled down as rulers, unless some of them were fanatically inclined to make forcible conversions, they left the Hindus in the hands of their religious leaders and, whenever they wanted to pacify them by quiet meth- ods, they made use of the Brahmans as their accredited represen- tatives.

Another great advantage was that, for the first time in histo- ry, all the peoples of India, of all sects and denominations, were brought under the supremacy of the Brahmans. Till then, they had claimed to be priests of only the three higher castes and did not presume to speak for the Shudras and other Indian peoples ex- cept to keep them at a safe distance. The Muhammadans called all the non-Muslim inhabitants, without any discrimination, by the common name “Hindu,” which practically meant non-Muslim and nothing more. This simple fact… condemned the dumb millions of the country to perpetual subjection to their priestly exploiters. Indians became “Hindus,” their religion became Hinduism, and Brahmans became their masters…. Brahmanism became Hindu- ism, that is, the religion of all who were not followers of the Proph- et of Mecca. Fortified thus in an unassailable position of sole reli- gious authority, Brahmans commenced to establish their theocratic

overlordship of all India.19

The Bhagats Seek Begampura — In the 12th century, at the outset of the Delhi Sultanate, lived Farid. A Sufi Muslim born in Punjab and one of the earliest Bhagats who preceded Guru Nanak, Farid faced the dark condition of the Indian subcontinent with calmness as he taught a path of love rooted in human worth. Amidst great sociopolitical upheaval, Farid declares, “The Lord Eternal in all abides: Break no heart – know, each being is a priceless jewel.”20

Championing the equally divine origins of all humanity, he proclaims, “The Creation is in the Creator, and the Creator is in the Creation.”21 For Farid, because of the inherent sacredness of all creatures, no one is an infi- del or an Untouchable. While the majority of the population languished un- der a system that called them outcastes, he suggested the way to cast out the hatred practiced by the elites was to respond with love. As Farid says, “Do not turn around and strike those who strike you with their fists.”22 Instead, he admonishes, “Return thou good for evil, bear no revenge in thy heart.”23 Over ensuing centuries, other Bhagats charted paths to guide the most

wretched members of society towards freedom.

Bhagat Namdev (c. 1270-1350), a tailor and poet from Maharashtra, asks, “What do I have to do with social status? What do I have to do with ancestry?”24 He believed God cares for all humans, no matter their flaws. He writes, “You saved the prostitute and the ugly hunch-back.”25

This simple-hearted saint, who knew that all people are created equal, was himself regularly treated as inferior. Describing his experience being thrown out of a temple, he writes, “Calling me low-caste and Untouchable, they beat me and drove me out; what should I do now, O Beloved Father Lord? If You liberate me after I am dead, no one will know that I am liber- ated.”26 In another verse about being ejected from a temple because of his caste, he expresses the pain and injustice felt by all the Mulnivasi as he cried out to his Creator.

ਹਸਤ ਖੇਲਤ ਤੇਰੇ ਦੇਹੁਰੇ ਆਇਆ ॥ ਭਗਿਤ ਕਰਤ ਨਾਮਾ ਪਕਿਰ ਉਠਾਇਆ ॥ ਹੀਨੜੀ ਜਾਿਤ ਮੇਰੀ ਜਾਿਦਮ ਰਾਇਆ ॥ ਛੀਪੇ ਕੇ ਜਨਿਮ ਕਾਹੇ ਕਉ ਆਇਆ ॥

ਲੈ ਕਮਲੀ ਚਿਲਓ ਪਲਟਾਇ ॥ ਦੇਹੁਰੈ ਪਾਛੈ ਬੈਠਾ ਜਾਇ ॥

Laughing and playing, I came to Your Temple, O Lord. While Namdev was worshipping,

he was grabbed and driven out.

I am of a low social class, O Lord;

why was I born into a family of fabric dyers? I picked up my blanket and went back,

to sit behind the temple.27

In the 15th century, a weaver from Uttar Pradesh named Bhagat Kabir (c. 1398-1448) voiced the equality of all which is found in the mortality of all. He writes, “The king and his subjects are equally killed; such is the power of Death.”28 Whether a person is considered high born or low born, all enter and leave the world in the same way, as he states, “Naked we come, and naked we go. No one, not even the kings and queens, shall remain.”29 Consequently, he denounces the concept of hereditary caste in a verse op- posing the superiority of Brahmans.

ਗਰਭ ਵਾਸ ਮਿਹ ਕੁਲੁ ਨਹੀ ਜਾਤੀ ॥ ਬ੍ਹਮ ਿਬੰਦੁ ਤੇ ਸਭ ਉਤਪਾਤੀ ॥੧॥ ਕਹੁ ਰੇ ਪੰਿਡਤ ਬਾਮਨ ਕਬ ਕੇ ਹੋਏ ॥ ਬਾਮਨ ਕਿਹ ਕਿਹ ਜਨਮੁ ਮਤ ਖੋਏ ॥ ਜੌ ਤੂੰ ਬ੍ਾਹਮਣੁ ਬ੍ਹਮਣੀ ਜਾਇਆ ॥ ਤਉ ਆਨ ਬਾਟ ਕਾਹੇ ਨਹੀ ਆਇਆ ॥ ਤੁਮ ਕਤ ਬ੍ਾਹਮਣ ਹਮ ਕਤ ਸੂਦ ॥ ਹਮ ਕਤ ਲੋਹੂ ਤੁਮ ਕਤ ਦੂਧ ॥

In the dwelling of the womb, there is no ancestry or social status. All have originated from the Seed of God.

Tell me, O Pandit, O religious scholar:

since when have you been a Brahman?

Don’t waste your life by continually claiming to be a Brahman. If you are indeed a Brahman, born of a Brahman mother,

Then why didn’t you come by some other way?

How is it that you are a Brahman, and I am of a low social status? How is it that I am formed of blood, and you are made of milk?30

Guru Ravidas (1450-1520), a contemporary of Guru Nanak, was a cob- bler who, like Bhagat Kabir, was also from Uttar Pradesh. He continued

spreading ideals against social division by declaring one Creator God who loves His creatures equally regardless of the caste his followers were born into. He proclaims, “Whether he is a Brahman, a Vaishya, a Shudra, or a Kshatriya; whether he is a poet, an outcaste, or a filthy-minded person, he becomes pure by meditating on the Creator.”31

Instead of a segregated society, in which the masses live in fear of their shadows because they are divided into castes of increasingly degraded val- ue, Bhagat Ravidas presents a vision of an heavenly city where all are equal and free.

ਬੇਗਮ ਪੁਰਾ ਸਹਰ ਕੋ ਨਾਉ ॥ ਦੂਖੁ ਅੰਦੋਹੁ ਨਹੀ ਿਤਿਹ ਠਾਉ ॥ ਨਾਂ ਤਸਵੀਸ ਿਖਰਾਜੁ ਨ ਮਾਲੁ ॥

ਖਉਫੁ ਨ ਖਤਾ ਨ ਤਰਸੁ ਜਵਾਲੁ ॥ ਅਬ ਮੋਿਹ ਖੂਬ ਵਤਨ ਗਹ ਪਾਈ ॥ ਊਹਾਂ ਖੈਿਰ ਸਦਾ ਮੇਰੇ ਭਾਈ ॥ ਕਾਇਮੁ ਦਾਇਮੁ ਸਦਾ ਪਾਿਤਸਾਹੀ ॥ ਦੋਮ ਨ ਸੇਮ ਏਕ ਸੋ ਆਹੀ ॥ ਆਬਾਦਾਨੁ ਸਦਾ ਮਸਹੂਰ ॥

ਊਹਾਂ ਗਨੀ ਬਸਿਹ ਮਾਮੂਰ ॥

ਿਤਉ ਿਤਉ ਸੈਲ ਕਰਿਹ ਿਜਉ ਭਾਵੈ ॥

Begampura, “the city without sorrow,” is the name of the town.

There is no suffering or anxiety there.

There are no troubles or taxes on commodities there.

There is no fear, blemish, or downfall there.

Now I have found this most excellent city.

There is lasting peace and safety there, O Siblings of Destiny. God’s Kingdom is steady, stable and eternal.

There is no second or third status; all are equal there. That city is populous and eternally famous.

Those who live there are wealthy and contented. They stroll about freely, just as they please.32

Guru Nanak’s Panth — Under the guidance of Guru Nanak, these liberating messages were united as the foundational doctrines of the Sikh Revolution. As a Sikh, Guru Nanak exhausted all points of travel in his mis- sion to discover truths that might topple tyranny. Traveling to the East as far

as Assam and Burma, to the South as far as Sri Lanka, to the West as far as Mecca, and to the North into Tibet and China, he listened, learned, and di- alogued. In the process, he constructed an institution called the Panth with the intention of overturning the conventions of falsehood which enslaved the common people of the Indian subcontinent. His vision was to give them (and those beyond the subcontinent) a guiding light for the future.

In his lifetime, new burdens were placed upon the downtrodden as armed foreign invaders again swept into India. Since the 12th century, the Bhagats had challenged Brahmanism by composing poetry, dialoguing, and educating the masses. In the 16th century, however, circumstances dete- riorated further as Babur — the “tiger” who founded the Mughal Empire

— conquered Afghanistan and then swept through northern India to seize Delhi.

Historically, the Brahmanical strategy for survival was alliance with invaders. With the arrival of the Mughals, the voice of the Mulnivasi risked total strangulation as Brahmans united with the State to suppress any strain of resistance. The “lowest of the low” faced a two-headed hawk — one head being the Mughals, who devoured the people’s possessions; the other head being the Brahmans, who devoured the people’s souls. Thus, as Guru Nanak recognized these fresh challenges placed on the backs of the Mulnivasi, he developed the Panth as a new and relevant institution — a unique path en- tirely distinct from any other existing tradition.

A hallmark of the Panth was its condemnation of both social and po- litical tyrannies. Setting the precedent of resistance to tyranny, Guru Nanak observed the bloodshed perpetrated by the Mughal invaders and mournfully provided his eyewitness account.

Babur terrified Hindustan. The Creator Himself does not take the blame, but has sent the Mughal as the messenger of death. There was so much slaughter that the people screamed. Didn’t You feel compassion, Lord? O Creator Lord, You are the Master of all. If some powerful man strikes out against another man, then no one feels any grief in their mind. But if a powerful tiger attacks a flock of sheep and kills them, then its master must answer for it. This priceless country has been laid waste and defiled by dogs, and no one pays any attention to the dead.33

As he denounced the invasion, Guru Nanak developed a policy of the

Panth which would be carried forward by his successors for generations. As he lamented the brutal subjugation of Hindus and Muslims alike, he emerged as an equal opportunity activist for all oppressed peoples. He not only exposed the exploitations of Brahmanism, but also raised his voice in protest against the atrocities committed by the State. As the powerful waged war for territorial control, he warned those caught in the confluence of events.

He writes, “You are engrossed in worldly entanglements, O Siblings of Destiny, and you are practicing falsehood.” Ultimately, Babur’s massacres led the Guru to conclude that the fact of human mortality reveals the value of things of an eternal rather than a temporary nature. The atrocities, as he describes, inspired him to call out to the Creator for hope.

Those heads adorned with braided hair, with their parts painted with vermillion. Those heads were shaved with scissors, and their throats were choked with dust. They lived in palatial mansions, but now they cannot even sit near the palaces…. They came in palanquins, decorated with ivory. Water was sprinkled over their heads, and glittering fans were waved above them. They were giv- en hundreds of thousands of coins when they sat, and hundreds of thousands of coins when they stood. They ate coconuts and dates and rested comfortably upon their beds. But ropes were put around their necks, and their strings of pearls were broken. Their wealth and youthful beauty, which gave them so much pleasure, have now become their enemies. The order was given to the soldiers, who dishonored them, and carried them away….

Since Babur’s rule has been proclaimed, even the princes have no food to eat. The Muslims have lost their five times of daily prayer, and the Hindus have lost their worship as well. Millions of religious leaders failed to halt the invader,when they heard of the Emperor’s invasion. He burned the rest-houses and the ancient temples; he cut the princes limb from limb, and cast them into the dust. None of the Mughals went blind, and no one performed any miracle. The battle raged between the Mughals and the Pathans, and the swords clashed on the battlefield. They took aim and fired their guns, and they attacked with their elephants…. The Hindu women, the Muslim women, the Bhattis and the Rajputs, some had their robes torn away, from head to foot, while others came

to dwell in the cremation ground. Their husbands did not return home….

The body shall fall, and the soul shall depart; if only they knew this. Why do you cry out and mourn for the dead? The Lord is, and shall always be. You mourn for that person, but who will mourn for you? You are engrossed in worldly entanglements, O Siblings of Destiny, and you are practicing falsehood. The dead person does not hear anything at all; your cries are heard only by other people. Only the Lord, who causes the mortal to sleep, O Nanak, can awaken him again. One who understands his true home does not sleep. If the departing mortal can take his wealth with him, then go ahead and gather wealth yourself…. I have searched in the four directions, but no one is mine. If it pleases You, O Lord Master, then You are mine, and I am Yours. There is no other door for me; where shall I go to worship? You are my only Lord; Your True Name is in my mouth.34

Thus, Guru Nanak lived in a land caught between the rival and equally vicious forces of Islamic invaders and the Brahmans. Amidst this chaos, he constructed the Panth. In the process, he denounced virtually every ortho- doxy of Brahmanism — caste, fundamentalism, the practice of sati, prohi- bition of remarriage by widows, degradation of women, the dowry system, the hypocrisy of empty rituals, and a culture of brutal subjugation of the masses by a handful of elite.

The masses flocked to this new “shop” as they joined the Guru’s rev- erence for reason and celebrated the equality and liberty produced by this freedom from delusion. This new shop, which grew warm with “traffic” over time, was giving away freedom. When the shop opened, however, its chief competition was the shops of the Brahmans which peddled supersti- tion.

Praising the establishment of Sikhism as “a highly important event,” British historian Edward Thornton simultaneously describes Brahmanism as “a vast system of superstition, probably the most influential, as well as the most tyrannical and mischievous, that has ever enthralled and depraved human nature.”35 A principal way in which Brahmanism enthralled human nature was through its myriad of idols. Then as now, idol-worship was pro- moted by Brahmans — the priests and curators of the temples which housed the idols — as the cornerstone of devotion.

The premier example of how Brahmanism harnessed the superstitions of the masses to control and exploit them was the floating Shiva-linga idol at Somnath Temple in Gujarat. Among the many smoke and mirrors exper- iments fraudulently thrusted on the public throughout the long annals of human history, the idol at Somnath stands out as one of the most successful attempts to fleece people of their wealth and dignity.

Although suspended by a scientifically-advanced magnetic levita- tion mechanism, the idol was mischievously portrayed as supernaturally self-levitating. Worshippers came from far and wide to pay to see this mar- vel. The idol’s secret was discovered in 1024, however, when the temple was captured by the invading army of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni. Persian scientist Zakariya al-Qazwini simultaneously describes the idol and its fate, writing,

The idol was in the middle of the temple without anything to sup- port it from below, or suspend it from above. It was regarded with great veneration by the Hindus, and whoever beheld it floating in the air was struck with amazement, whether he was a Mussulman or an infidel….

Everything that was most precious was brought there as of- ferings, and the temple was endowed with the taxes gathered from more than ten thousand villages. There is a river, the Ganges, which is held sacred…. They used to bring the water of this river to Somnath every day and wash the temple with it. A thousand Brah- mans were employed in worshipping the idol and attending on the visitors and five hundred damsels sang and danced at the door — all these were maintained upon the endowments of the temple. The edifice was built upon fifty-six pillars of teak, covered with lead…. When… [Mahmud of Ghazni] asked his companions what they had to say about the marvel of the idol, and of it staying in the air without prop or support, several maintained that it was upheld by some hidden support. The king directed a person to go and feel all around above and below it with a spear, which he did, but met with no obstacle. One of the attendants then stated his opinion that the canopy was made of loadstone [magnetite], and the idol of iron, and that the ingenious builder had skillfully contrived that the magnet should not exercise a greater force on any one side — hence the idol was suspended in the middle…. Permission was ob-

tained from the Sultan to remove some stones from the top of the canopy to settle the point. When two stones were removed from the summit, the idol swerved on one side; when more were taken away, it inclined still further, until at last it rested on the ground.36

How could human intelligence so easily fall prey to such a scam? The masses were an easy target for such frauds because, for generation after generation, the caste status imposed on them denied them access to even ba- sic education. According to caste laws, they were forbidden to obtain educa- tion. All learning was preserved in the Sanskrit language. As explained by 17th-century French physician François Bernier, who lived in the Mughal Empire, Sanskrit signified “pure language.” The Brahmans “call it the holy and divine language,” and it was “a language known only to the Pandits, and totally different from that which is ordinarily spoken in Hindustan.”37 With all knowledge kept under lock and key, the common people remained in a state of abject ignorance.

The elites isolated their community, banned others from learning their language, and propagated religious teachings forbidding non-Brahmans from accessing education. An educated public was to their disadvantage. “The Brahmans encourage and promote these gross errors and supersti- tions to which they are indebted for their wealth and consequence,” wrote Bernier. “As persons attached and consecrated to important mysteries, they are held in general veneration, and enriched by the alms of the people.”38

In the midst of this cultural context arose Farid, Namdev, Kabir, Rav- idas, and Nanak, who denounced the exploitive system of Brahmanism, taught that all are made equal and free in the sight of our Creator, and pre- sented a hopeful vision of a city without sorrow called Begampura. They championed the premier importance of embracing universal human dignity and reaching out to those who are considered low born. Furthermore, they taught that idol-worship is foolish because it involves humans worshipping their own lifeless creations. Idols cannot respond to those who cry out for help. As Guru Nanak advises,

ਿਹੰਦੂ ਮੂਲੇ ਭੂਲੇ ਅਖੁਟੀ ਜਾਂਹੀ ॥ ਨਾਰਿਦ ਕਿਹਆ ਿਸ ਪੂਜ ਕਰਾਂਹੀ ॥ ਅੰਧੇ ਗੁੰਗੇ ਅੰਧ ਅੰਧਾਰੁ ॥

ਪਾਥਰੁ ਲੇ ਪੂਜਿਹ ਮੁਗਧ ਗਵਾਰ ॥

ਓਿਹ ਜਾ ਆਿਪ ਡੁਬੇ ਤੁਮ ਕਹਾ ਤਰਣਹਾਰੁ ॥੨॥

The Hindus have forgotten the Primal Lord;

they are going the wrong way…. They are worshipping idols. They are blind and mute, the blindest of the blind.

The ignorant fools pick up stones and worship them. But when those stones themselves sink,

who will carry you across?39

Instead of seeking God in statues set in temples, the Bhagats agreed that people must recognize the presence of “the Lord’s Light in all.” With the arrival of the Mughals, however, a unique institution was necessary to continue propagating this teaching. Thus, Guru Nanak conceived the Panth. The response to the teachings of the Panth was revolutionary. Ratio- nality replaced superstition. Enlightenment replaced delusion. Exposition replaced exploitation. Liberty replaced tyranny. In contrast to the “system of superstition” propagated by Brahmanism, humanitarian Puran Singh

(1881-1931) writes,

Guru Nanak condemns false creeds and crooked politics and the unjust social order. He condemns the hollow scriptures and isms of the times; he condemns barren pieties, asceticisms, trances, sound-hearing yogas, bead-telling, namazes’ fasts, and all the for- mal vagaries of religious and political hypocrisies. He condemns them without sparing any, for it was all darkness in the world.…

Guru Nanak takes up, like a giant, the long-rooted conven- tions of Hindu and Muslim on the palm of his hand and pitches them into the sea. Off with cant. Away with nonsense. Down with lies….

Here, in the Punjab, was the wholesale destruction of all such systems in a glance, in a smile, in a presence. Down with the dead form and the evil minded social order. Down with false Islam and false Hinduism; take to the true creeds.40

Most notably, Guru Nanak reached out to the “lowest of the low.” In- dian historian Dr. Rajkumar Hans explains, “The Sikh Guru embraced Un- touchables by distinctly aligning himself with them to challenge the Hindu caste system. He destroyed the Hindu hierarchical systems — social as well as political.”41

The Guru chose to live as a son of the soil, exemplifying his teachings

by taking up a profession of honest labor. “Truth is higher than everything; but higher still is truthful living,” he taught.42 “Guru Nanak cast off the cos- tume of a hermit and spent the last 18 years of his life as a householder at Kartarpur,” reports Sangat Singh. There, in a town he founded in 1522, he worked as a farmer.

Here, he set up a human laboratory to practice the new faith, the Sikh Panth, to give practical shape to his over two decades of teachings…. Here was Guru Nanak, tilling the land, living with his wife and sons, preaching the name of God and his philosophy, a positive reaffirmation of all human beings and their right to a dignified life, free from religious coercion, social bondage, and political oppression.43

As Guru Nanak denounced unjust social orders, challenged invaders, and showed the path to emancipation through the “true creeds” of equal- ity and liberty, he set the stage for his successors. For 169 years after his death, nine Sikh Gurus continued his sacred mission to institutionalize the Mulnivasi’s centuries of struggle for liberation. In place of “false creeds and crooked politics” which taught elitism and entrenched oppression, these Gurus introduced and cultivated teachings of human dignity. They brought mental, spiritual, and physical liberty to an oppressed community. As a re- sult, in the words of Guru Arjun, “The egg of superstition has burst; the mind is illumined: the Guru has shattered the fetters of the feet and freed the captive.”44

With the advent of the tenth Guru, Gobind Singh, and his establish- ment of the Khalsa in 1699, the original intent of Guru Nanak was finally fulfilled. The downtrodden embraced a Panth in which they will never be victims, always be victorious, and constantly fight for the oppressed. First, however, it was destined for Arjun, the fifth Guru, to sacrifice his life.

Citations

1 Madra, Amandeep Singh and Parmjit Singh (eds.). “Sicques, Tigers, or Thieves”: Eye- witness Accounts of the Sikhs. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. 2004. 4.

2 Cole, W. Owen and Piara Singh Sambhi. A Popular Dictionary of Sikhism. 1990. Lon- don: Routledge. 1997. 3.

3 Guru Granth Sahib. 15.

4 Ibid., 349.

5 Ibid., 376.

6 Ibid., 300.

7 Ibid., 5.

8 Ibid., 432.

9 Usage of terms “Bhagats and Gurus” should in no way be construed as placing the status of one above the other. Both terms are equal in accordance with the teachings of Guru Granth Sahib.

10 Weber, Max. The Religion of India: The Sociology Of Hinduism And Buddhism. Glen- coe: The Free Press. Tr. by Gerth, Hans H. and Don Martindale. 1958. 29-30.

11 Theertha, Dharma Swami. History of Hindu Imperialism. 1941. Kottayam, Kerala: Ba- basaheb Ambedkar Foundation. 1992. 6.

12 Ibid., 6-7.

13 Ibid., 76-77.

14 Singh, Sangat. The Sikhs in History. 1995. Amritsar: Singh Brothers. 2005. 4.

15 Ibid., 5.

16 Theertha. History. 100-101.

17 Srivastava, Ashirbadi Lal. The Sultanate of Delhi. 1950. Agra: Shiva Lal Agarwala & Company. 1966. 17.

18 Tavernier, Jean Baptiste. Travels in India (vol. 2). V. Ball (tr.). London: Macmillan and Co. 1889. 181.

19 Theertha. History. 114.

20 Granth. 1384.

21 Ibid., 1350.

22 Ibid., 1378.

23 Ibid., 1381.

24 Ibid., 485.

25 Ibid., 345.

26 Ibid., 1292.

27 Ibid., 1164.

28 Ibid., 855.

29 Ibid., 1157.

30 Ibid., 324.

31 Ibid., 858.

32 Ibid., 345.

33 Ibid., 360.

34 Ibid., 417-418.

35 Thornton, Edward. A Gazetteer of the Territories Under the Government of the East-In- dia Company and of the Native States on the Continent of India. London: Wm. H. Allen & Co. 1858. 911.

36 Jackson, A.V. Williams (ed). A History of India (Vol. 9). London: The Grolier Society. 1906. 201-203.

37 Bernier, François. Travels in the Mogul Empire: A.D. 1656-1668. Archibald Constable (Tr.). London: Oxford University Press. 1916. 335.

38 Ibid., 305.

39 Granth. 556.

40 Singh, Puran. Spirit of the Sikh (Vol 2, Part 2). Patiala: Punjabi University. 1981. 3-4.

41 Rawat. Studies. 134.

42 Granth. 62.

43 Singh. Sikh. 20.

44 Granth. 1002.

— 2 —

Guru Arjun Carries the Caravan Forward

A succession of Gurus after Nanak expanded on the vision of Begampu- ra — the city without sorrow. Like his predecessors, Guru Arjun, the fifth Guru, boldly denounced the Brahmanical caste system taught by the Shas- tras (Hindu scriptures). Like the sons and daughters of the soil in whose footsteps he followed, he was tasked with the mission of “moving the cara- van forward” — that is, progressing the emancipation of the downtrodden.

Under the patronage of his father, Guru Ram Das (1534-1581), Arjun was prepared to sacrifice himself for the sake of the despised and deprived. His mother, Bibi Bani, was also central to preparing her son and inspiring the generations which followed in his footsteps. Summing up the importance of family and a mother’s role in nurturing her children, Guru Arjun writes, “O son, this is a mother’s blessing, that you may never even for a mere moment forget the Creator, forever worshipping the Lord of the Universe.”1 In turn, Guru Arjun prepared his son, Hargobind, to sacrifice himself.

As he was called to sacrifice, the Guru was not naive to the difficulty of his assignment or the dangers it entailed. Yet he knew he must fulfill his duty at any cost — even at the cost of his life.

Guru Arjun’s legacy included two of the most significant achievements of the Panth. First, the completion in Amritsar, Punjab of Harmandir Sahib. Second, he compiled the Adi Granth (the Sikh noble book which eventually became the Guru Granth) and installed it in the completed Gurdwara.

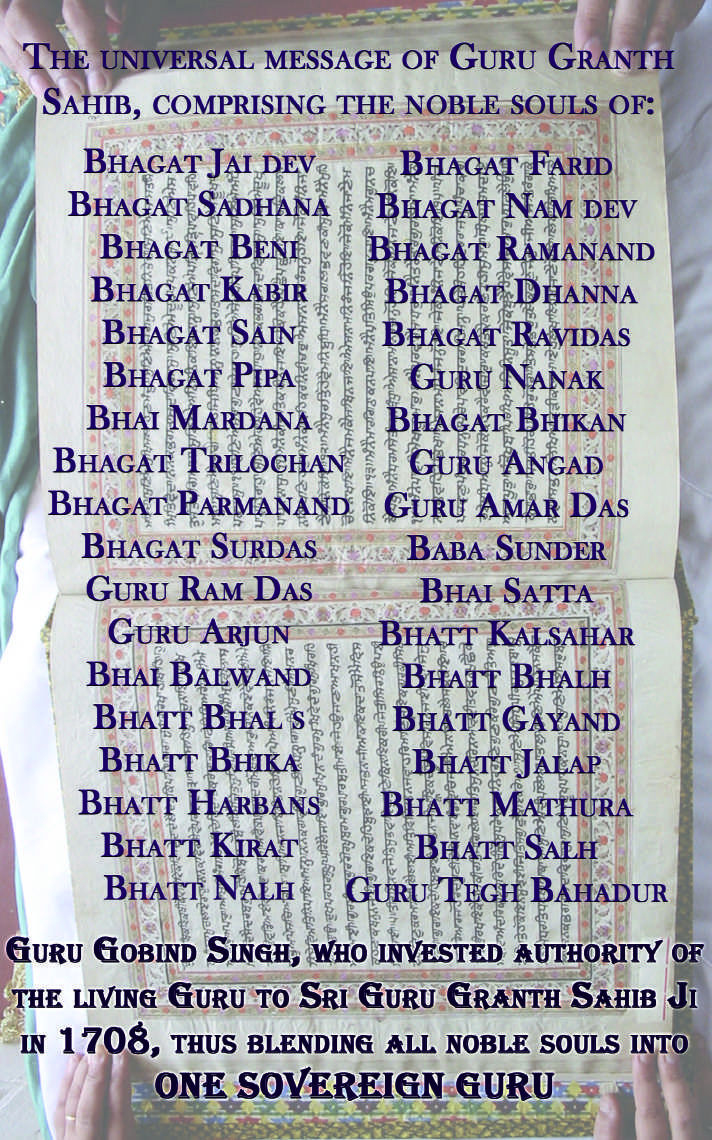

“Guru Granth Sahib, the sacred text of the Sikhs, consists of the com- positions of six of the ten Sikh gurus and contributions of fifteen Sikh bards and fifteen non-Sikh sant poets of various social, ethnic, and religious back- grounds, including the eminent Muslim Sufi, Sheikh Farid,” explains Dr. Rajkumar Hans. “This makes the sacred text an inclusive expression of spir- ituality in the history of world religions.”2

Guru Arjun became the Steward of Begampura as he compiled the Adi Granth by collecting the writings of Farid, Namdev, Kabir, Ravidas, Nanak,

and many other Bhagats. Guided by the Shabads (hymns) recorded in the Adi Granth, the Guru put the wisdom of the saints into practice. At this time, he was the leading light who took upon himself the duty to guide the Mulnivasi in a victorious march towards freedom.

In a dark age, Guru Arjun shouldered the tremendous burden of pre- serving the flickering flame of Begampura to shine hope for the wretched. Standing against the flow of history, the Guru yelled “stop” in the faces of the Brahmans and Mughals who collaboratively trampled the commoners under their feet. As Guru Nanak counseled, this was a dangerous position to hold.

ਜਉ ਤਉ ਪ੍ੇਮ ਖੇਲਣ ਕਾ ਚਾਉ ॥

ਿਸਰੁ ਧਿਰ ਤਲੀ ਗਲੀ ਮੇਰੀ ਆਉ ॥ ਇਤੁ ਮਾਰਿਗ ਪੈਰੁ ਧਰੀਜੈ ॥

ਿਸਰੁ ਦੀਜੈ ਕਾਿਣ ਨ ਕੀਜੈ ॥

If you desire to play this game of love with Me, Then step onto My Path with your head in hand. When you place your feet on this Path,

Give Me your head, and do not pay any attention to public opinion.3

Nonetheless, Guru Arjun was willing to sacrifice his head. Playing the game of love, he stepped onto the path with his head in his hand, sought the company of “the lowest of the low,” and ignored all the critics. Despite knowing the most brutal tortures awaited him, he embraced the opportunity to help the simple-hearted break the shackles placed upon them by the Brah- mans and Mughals. The ruling elites, as detailed in the words of Jahangir, perceived his “ways and manners” as a direct threat to their powerhouse.

For centuries, Brahmans secured their upper-echelon position by brutal maintenance of a totalitarian caste system which denied education, resourc- es, and fundamental human dignity to the masses — all under the guise of honoring religious tradition. These common people were the “simple-heart- ed” described by Jahangir as flocking to Guru Arjun. Meanwhile, as the Adi Granth’s message progressively chipped away at the power structure of the Brahmans, the Mughals expanded their rule over northern India. The down- trodden in both Hindu and Muslim communities found no hope in either religion and little difference between either creed. “Islam then established in India as a religion had become a tyranny,” explains Puran Singh.4 “It was

just lip profession.”

Despite these continued oppressions, the Panth flourished as it showed the people how to obtain spiritual, social, economic, and political liberty. As it flourished, Amritsar began to represent the people’s power. Essentially, it arose as the capital of a parallel government — the government of a nation of people who were subjects by choice, not birth. Autonomy, however, was intolerable to the ruling elites. British journalist Fergus Nicoll explains,

Jahangir was not willing to take any risk with such an influential Punjabi community leader; he also found it irritating that Arjun Dev and his predecessors had represented an alternative source of authority to his own dynasty ever since the early years of the Mughal invasion. It has been argued that Jahangir would ideally have liked to end Amritsar’s autonomy and force all Sikhs into the embrace of Islam, a recourse that would have been wholly objec- tionable to his father Akbar.5

Nicoll’s explanation that Guru Arjun “represented an alternative source of authority” was collaborated by Jahangir’s testimony about his reasons for ordering the Guru’s execution. The Guru, wrote Jahangir, was “in the garb of Pir [saint] and Sheikh [king].” Thus, Guru Arjun was manifesting both temporal and spiritual authority.

Nicoll’s description of Guru Arjun as an “influential Punjabi communi- ty leader” was collaborated by Father Jerome Xavier, a Jesuit priest living in the Mughal court. Describing Guru Arjun in a September 1606 letter, Fr. Xavier writes, “[He was] a Gentile called Guru, who amongst the Gentiles is like the Pope amongst us. He was held as a saint and was as such venerat- ed.” The Guru’s reputation, notes Xavier, was of “high dignity.”

Mughal-Brahman Co-Rule — Efforts to eliminate this man of “high dignity” owed their origins to a joint alliance between the Mughals and the Brahmans.

The caste system enabled India’s subjugation by foreign invaders. Ac- cording to Lieutenant Colonel John Malcolm of the British East India Com- pany, “The Muhammadan conquerors of India… saw the religious prejudic- es of the Hindus, which they had calculated upon as one of the pillars of their safety.”6 Meanwhile, alliance with the Mughals benefited the Brahmans as it enabled them to protect themselves, maintain sociopolitical power, and continue to impose the caste system with the sanction of the Mughals.

Consequently, Brahmans were welcomed as key members of the Mu- ghal government and they were more than willing to fill those positions. American historian Dr. Audrey Truschke explains, “The Mughal elite poured immense energy into drawing Sanskrit thinkers to their courts, adopting and adapting Sanskrit-based practices, translating dozens of Sanskrit texts into Persian and composing Persian accounts of Indian philosophy.”7 Seizing the chance to maintain their stranglehold on social power, Brahmans (already the wealthiest and most-educated by virtue of their position in the caste sys- tem) “became influential members of the Mughal court, composed Sanskrit works for Mughal readers, and wrote about their imperial experiences.”8

Some of the most prominent of these “Sanskrit thinkers” were Birbal (1528–1586), Bhagwant Das (1537-1589), Todar Mal (died 1589), Pandit Jagannath (1590-1641), Raghunath Ray Kayastha (died 1663), Chandar Bhan Brahman (died c. 1670), and Bhimsen Saxena (lived c. 1700). Birbal and Bhagwant Das were generals under Akbar. Todar Mal was the Chief Finance Minister under Akbar. Jagannath was a poet under Jahangir and Shah Jahan. Raghunath was a Finance Minister (eventually Chief Finance Minister) under Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb. Chandar Bhan was a munshi (secretary) under Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb. Bhimsen was a general under Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb.

While these men stood out as prominent examples of the partnership between Brahmans and Mughals, they represent a mere handful of the many others who joined in the Mughal-Brahman co-rule of India. The backbone of the civil service was composed of upper-caste Hindus. “From the middle of the 17th century onwards, most of the munshis were Hindus, and their proportion rapidly increased,” writes Indian historian Jadunath Sarkar. “The Hindus had made a monopoly of the lower ranks of the revenue department (diwani) from long before the time of Todar Mal.”9

The privileged castes not only swelled the civil service ranks of the Mughals, but they also provided much of the muscle for the imperial mili- tary. In particular, the high-caste Rajputs stepped forward to exercise force on behalf of the Empire. Indian historian Satish Chandra reports,

The policy of seeking a special relationship with the Rajputs emerged under Akbar, and was one of the most abiding features of Mughal rule in India….

Apart from being loyal allies, the Rajputs begin to emerge as the sword-arm of the empire…. The Rajputs emerge as partners in

the kingdom….

The Rajputs not only emerged as dependable allies who could be used anywhere for fighting, even against princes of blood, they also began to be employed in tasks of governance….

The Mughal-Rajput alliance was mutually beneficial…. The steadfast loyalty of the Rajputs was an important factor in the con- solidation and further expansion of the Mughal empire. On the other hand, service in the Mughal empire enabled the Rajput rajas to serve in distant places far away from their homes, and to hold important administrative posts. This further raised their prestige and social status. Service with the Mughals was also financially rewarding. beginning with Akbar.10

On one hand, this dual alliance between two oppressive systems created fertile ground for the growth of the doctrines of the Gurus. “Sikhism arose where fallen and corrupt Brahmanical doctrines were most strongly acted on by the vital and spreading Muhammadan belief,” wrote Scottish histori- an Joseph Davey Cunningham in 1849.11 On the other hand, when Sikhism emerged as the subcontinent’s leading defender of the doctrine of human dignity, it provoked the wrath of both the Mughals and the Brahmans.

Just as in times past when Brahmans collaborated with foreign invad- ers during the eradication of Buddhism, they again joined forces with the occupying Mughals. The Mughal Empire was established in 1526. By the mid-1500s, Brahmans began employing their intimate relationship with the Mughals to attempt to instigate the State against the Sikhs.

According to British historian Max Arthur Macauliffe, who wrote a six-volume history of the Sikhs, a group of Brahmans approached Emperor Akbar (1542-1605) to lodge a complaint against the third Sikh Guru, Amar Das (1479-1574). The basis of their grievance was the Guru’s opposition to caste. As Macauliffe reported, the Brahmans told Akbar:

Thy Majesty is the protector of our customs and the redresser of our wrongs…. Guru Amar Das of Goindwal hath abandoned the religious and social customs of the Hindus, and abolished the dis- tinction of the four castes. Such heterodoxy hath never before been heard of…. There is now no twilight prayer, no gayatri [Sanskrit hymns], no offering of water to ancestors, no pilgrimages, no ob- sequies, and no worship of idols…. The Guru hath abandoned all

these, and established the repetition of Waheguru instead of Ram; and no one now acteth according to the Vedas or the Smritis. The Guru reverenceth not Jogis [yogis], Jatis [castes], or Brahmans. He worshippeth no gods or goddesses, and he ordered his Sikh to refrain from doing so forevermore. He seateth all his followers in a line, and causeth them to eat together from his kitchen, irre- spective of caste — whether they are Jats, strolling minstrels, Mu- hammadans, Brahmans, Khatris, shopkeepers sweepers, barbers, washermen, fishermen, or carpenters. We pray thee restrain him now, else it will be difficult hereafter. And may thy religion and Empire increase and extend over the world.12

Thus, the Mughal-Brahman alliance began with the Brahmans turning the attention of the Mughals to the distinct “ways and manners” of the warm shop of the Sikhs. Akbar did not act on their complaint, but the Brahmans continued attempting to use State power to undermine the rise of the Panth. In the late 1500s, their attempts expanded with Birbal.

Birbal — During the reign of Akbar, one of the “Sanskrit thinkers” drawn to the Mughal courts was Raja Birbal, a Brahman from Uttar Pradesh. Birbal was “Akbar’s constant companion for many years,” explained Indi- an historian Abraham Eraly. “A celebrated litterateur,” he was nicknamed “Kavi Rai, King of Poets” by Akbar.13 The Mughal and the Brahman were so close that the Emperor opened his mind to Brahmanism. According to Eraly, “When Raja Birbal became a major influence on Akbar, he… per- suaded the Emperor to worship the sun and the fire, and venerate ‘water, stones, and trees, and all natural objects, even down to cows and their dung; that he should adopt the sectarian mark, and the Brahmanical thread.”14

Birbal planted the seeds of conflict between the ruling elite and the Sikhs. “Birbal, a learned and accomplished man, was on religious grounds hostile to the Guru and jealous of his daily increasing influence and popu- larity,” writes Macauliffe.15 Corroborating Macauliffe’s perspective on Bir- bal, British historian Vincent Arthur Smith continues, “He was hostile to the Sikhs, whom he considered to be heretics.”16

In 1586, Akbar sent Birbal on a military campaign to subdue a rebel- lion in Afghanistan. First, the Brahman “made up his mind to harass the Guru and the people at Amritsar,” reports Sikh historian Prithi Pal Singh. He stopped in Punjab and, on the excuse of raising funds for his expedition, he “ordered his collectors to collect a fixed levy from the people of Punjab

with a special reference to Amritsar.” Guru Arjun replied that the Sikhs sought an exemption and, following his lead, the simple-hearted people of Amritsar refused to pay.17

Unable to delay his military campaign any longer, Birbal was forced to depart. “He ordered his staff to remind him of the Guru on his return, and said that if he did not then get a rupee from each house in Amritsar, he would raze the city to its foundations,” explains Macauliffe.18 However, he never got the chance to do so. According to American historian John F. Richards, during the Raja’s war in Afghanistan, “about 8,000 imperial sol- diers, including Raja Birbal, were killed in the greatest disaster to Mughal arms in Akbar’s reign.”19 The Sikhs, writes Smith, “consequently regard his miserable death as the just penalty for his threats of violence to Arjun.”20

According to Eraly, Akbar “avenged Birbal’s death by sending Todar Mal to hunt down the Afghans.”21 Bhagwant Das, meanwhile, was sent in 1586 to conquer Kashmir. Francisco Pelsaert, a 17th-century merchant with the Dutch East India Company, notes, “Raja Bhagwant Das overcame the country by craft and subtlety, the lofty mountains and difficult roads render- ing forcible conquest impossible.”22 Thus, while Guru Arjun was peacefully developing the Panth and the Granth in Punjab, Brahmans led armies in aggressive wars of conquest to expand the borders of the Mughal Empire.

Chandu Shah — Birbal planted seeds of conflict between Sikhs and the Empire. Twenty years after his death, the seeds were watered and even- tually harvested by another “Sanskrit thinker” named Chandu Shah, who worked as “the finance administrator of Lahore province.”23

Chandu is referenced in contemporary accounts of Guru Arjun’s per- secution — one in 1606 from Fr. Xavier and one in the mid-1600s from the Persian history Dabistan-i Mazahib. The accounts refer, respectively, to a “rich gentile” (a Hindu) and “collectors” who orchestrated the Guru’s torments.

Later accounts by agents of the British East India Company also ref- erence Chandu. In 1783, for instance, George Forster writes, “Arjun, who having incurred the displeasure of a Hindu (named Chandu) favored by Jahangir, was committed by that prince to the persecution of his enemy; and his death… was caused, it is said, by the rigor of confinement.”24 Writing in 1812, Lt. Col. Malcolm mentions Chandu as well, referring to him as “Danichand.”

The Adi Granth… was partly composed by Nanak and his imme-

diate successors, but received its present form and arrangement from Arjunmal, who has blended his own additions with what he deemed most valuable in the compositions of his predecessors. It is Arjun, then, who ought, from this act, to be deemed the first who gave consistent form and order to the religion of the Sikhs: an act which, though it has produced the effect he wished of uniting that nation more closely and of increasing their numbers, proved fatal to himself. The jealousy of the Muhammadan government was ex- cited, and he was made its sacrifice. The mode of his death… is related very differently by different authorities: but several of the most respectable agree in stating that his martyrdom, for such they term it, was caused by the active hatred of a rival Hindu zealot, Danichand Kshatriya, whose writings he refused to admit into the Adi Granth on the ground that the tenets in them were irrecon- cilable to the pure doctrine of the unity and omnipotence of God taught in that sacred volume. This rival had sufficient influence with the Muhammadan governor of the province to procure the imprisonment of Arjun; who is affirmed, by some writers, to have died from the severity of his confinement; and, by others, to have been put to death in the most cruel manner. In whatever way his life was terminated, there can be no doubt, from its consequences, that it was considered by his followers as an atrocious murder…. The Sikhs, who had been till then an inoffensive, peaceable sect, took arms under Hargobind, the son of Arjunmal.25

Chandu, who Malcolm describes as a “rival,” initially attempted to buy Guru Arjun’s allegiance by proposing the marriage of his daughter to the Guru’s son. However, Guru Arjun’s only desire was to liberate humanity. He saw through the scheme and understood the marriage proposal as a de- vious attempt to trap him, neutralize the Sikhs, and consolidate their power with that of the tyrants who ruled from the throne of Delhi. Writing a lit- tle over 100 years after the incident, 18th-century Indian author Seva Das reports that Chandu “was reeling from the rejection of the marriage of his daughter to the Guru’s son.” According to his account, “Chandu is identi- fied as feeding false reports against Guru Arjun, thereby contributing to his arrest and torture.”26

In his memoirs, Jahangir confesses to maintaining hawk-eyed surveil- lance of the Panth and desiring to put an end to their “false traffic.” The Em-

peror, who was already agitated by the Guru, was emboldened to act when the upper-caste State agent, Chandu, campaigned against the Guru. Once again, Brahman bureaucrats collaborated with Imperial forces to assail this irritating group of liberators. “The Guru was summoned to the Emperor’s presence, and fined and imprisoned at the instigation chiefly, it is said, of Chandu Shah, whose alliance he had rejected, and who represented him as a man of dangerous ambition,” reports Joseph Davey Cunningham.27

Guru Arjun’s “Objectionable Passages” — Subsequently, the cam- paign against Guru Arjun was joined by a broader coalition of Brahman and Mughal courtiers who felt equally endangered by the independence of the Sikh people as manifested in the Guru sitting in Amritsar at Harmandir Sa- hib. The elite were angered by this sovereign source of power and the eleva- tion it gave the oppressed. The power of the elite depended on suppressing the Mulnivasi Bahujan by maintaining both the Brahman’s caste system and the Mughal’s foreign occupation.

“The pandits and the qazis,” notes Macauliffe, “also thought it a favor- able opportunity to institute new proceedings against the Guru on the old charge of having compiled a book which blasphemed the worship and rules of the Hindus and the prayers and fastings of the Muhammadans.”28 Jahan- gir imposed a fine of 200,000 rupees on Guru Arjun as a condition for his freedom. The Guru’s followers offered to pay it, but he defied the Emperor’s demand and refused monetary assistance. Macauliffe reports, “As the Guru would not allow the fine to be paid, he was placed under the surveillance of Chandu. The qazis and Brahmans offered the Guru the alternative of being put to death or of expunging the alleged objectionable passages in the Granth Sahib and inserting the praises of Muhammad and of the Hindu deities.”29

What were these “objectionable passages”? The teachings of the Bhagats, who spoke against caste, defended the equality of all humanity, and shared their vision of Begampura were naturally offensive to these pow- erful people. Also objectionable was Guru Arjun’s teaching that royalty is attainable by even the commonest of people. For instance, the Guru writes,

ਸਗਲ ਪੁਰਖ ਮਿਹ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਪ੍ਧਾਨੁ ॥ ਸਾਧਿਸੰਗ ਜਾ ਕਾ ਿਮਟੈ ਅਿਭਮਾਨੁ ॥ ਆਪਸ ਕਉ ਜੋ ਜਾਣੈ ਨੀਚਾ ॥

ਸੋਊ ਗਨੀਐ ਸਭ ਤੇ ਊਚਾ ॥

ਜਾ ਕਾ ਮਨੁ ਹੋਇ ਸਗਲ ਕੀ ਰੀਨਾ ॥

ਹਿਰ ਹਿਰ ਨਾਮੁ ਿਤਿਨ ਘਿਟ ਘਿਟ ਚੀਨਾ ॥

He is a prince among men

Who has effaced his pride in the company of the good,

He who deems himself as of the lowly,

Shall be esteemed as the highest of the high.

He who lowers his mind to the dust of all men’s feet, Sees the Name of God enshrined in every heart.30

Guru Arjun asserts that a person is not noble because of any social status obtained through an accident of birth. Lineage and bloodlines are not the source of royalty. Instead, humility, self-sacrifice, and recognition of the divine image present in all people are the attributes by which a person can become a prince. He went even further, insisting a pauper can be a king — even the “king of the whole world.” All that is necessary is love. He writes,

ਬਸਤਾ ਤੂਟੀ ਝੁੰਪੜੀ ਚੀਰ ਸਿਭ ਿਛੰਨਾ ॥

ਜਾਿਤ ਨ ਪਿਤ ਨ ਆਦਰੋ ਉਿਦਆਨ ਭ੍ਿਮੰਨਾ ॥

ਿਮਤ੍ ਨ ਇਠ ਧਨ ਰੂਪ ਹੀਣ ਿਕਛੁ ਸਾਕੁ ਨ ਿਸੰਨਾ ॥ ਰਾਜਾ ਸਗਲੀ ਿਸ੍ਸਿਟ ਕਾ ਹਿਰ ਨਾਿਮ ਮਨੁ ਿਭੰਨਾ ॥

He who lives in a ruined hut, with all his clothes torn: Who has neither caste, nor lineage, nor respect,

Who wanders in the wilderness,

Who has no friend or lover, who is without wealth or beauty, And who has no relation or kinsmen,

Is yet the king of the whole world,

If his heart is imbued with the love of God.31

The Brahmans, who propagated their hereditary superiority based on an accident of birth, and Emperors, who premised their nobility on the same argument, were equally infuriated by Guru Arjun’s assault on their claims to supremacy. The Guru was no respecter of titles, or wealth, or power. Instead, he accorded royalty to those who demonstrate humility by making themselves the servants of the downtrodden. In his eyes, a man becomes a king by serving rather than being served. Leadership means being a servant instead of a dictator.

Guru Arjun developed this concept but he did not originate it. Sikh