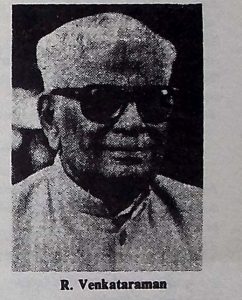

NEW DELHI, India, July 16, Reuter: Ramaswamy Venkataraman, elected today as India’s eighth President, is expected to give Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi an easier ride than his predecessor Zail Singh.

Venkataraman, 76, a lawyer, trade Union leader, editor and scholar, has been Vice-president since 1984 and in that post confirmed a lifelong reputation for fairness and integrity.

His nomination by Gandhi as the Congress (I) Party candidate ensured his election as nonexecutive Head of State, as the ruling Party has huge majorities in both Houses of Parliament, and controls 15 of the 25 Indian State Assemblies.

The members of the Parliament and the State Assemblies together comprise the Presidential electoral college.

After months of embarrassing public wrangles with Singh over the President’s constitutional powers, Gandhi can expect fewer arguments from Venkataraman when he takes office on July 24.

“Under the Constitution the President has no powers….. nothing can be done against the Prime Minister”, he said’ in a magazine interview published today.

But the Prime Minister may find that the new President is not his man — or anybody’s.

Venkataraman as Chairman of the Rajya Sabha (Upper House of Parliament) fended off opposition moves to censure Gandhi, but also criticized the government when he felt it necessary.

He permitted debate on the Presidential powers during the recent controversy as long as members avoided mentioning the protagonists by name.

Jailed by the British during India’s independence struggle, he nonetheless acknowledged their historical links by writing to the clerk of the House of Commons in London to ascertain British practice in Constitutional issues.

Born in the southern State of Tamil Nadu on December 4, 1910, Venkataraman studied as a lawyer and was an advocate in the Madras High Court.

His interest in Labour law led to leadership of several unions, including those of railway workers, dock workers and journalists. His trade union activities in turn led to involvement in India’s freedom struggle.

In 1942 he was imprisoned for two years for participation in the “Quit India” movement.

After World War two he defended Indians charged by the British with collaboration with the Japanese, and in 1950 entered the provisional post-independence Parliament.

Although a lifetime member of the Congress Party, the respect he commands there is as much for being among the dwindling band who fought for India’s freedom as for his political achievements.

He returned to State politics in Tamil Nadu for 10 years from 1957 and afterwards served on a number of governmental bodies including India’s key planning commission.

Only in the last decade did he achieve national prominence, becoming Finance Minister and Define Minister before accepting the Vice-presidency by vote of the Upper House.

Article extracted from this publication >> July 24, 1987