WITH the dust still settling over the newly ruined Akhal Takht, the eyes of Sikhs everywhere were suddenly opened. June 6, 1984, marked the end of a kind of innocence hitherto manifested by the Sikh community. The realization hit them hard, that what had seemed not to matter did, in fact, matter a great deal; that even though they knew themselves to be a separate religious entity, the Indian constitution did not distinguish them from Hindus. While Sikhs in India came to grips with the outrages perpetrated on the Golden Temple and 39 other gurdwaras in the Punjab, Sikhs in California and the rest of the U.S. and Canada faced another kind of dilemma. Almost no one knew who they really were. The US. Press, predictably, characterized the martyred Snat Bhindranwale as a sort of Ayatollah and the Sikhs as a tiny material sect of Hinduism. Sikhs scrambled to put their most articulate spokespeople before media interviewers in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Sacramento, Stockton, Yuba City and elsewhere. Press representatives, accustomed to interviewing religious leaders such as the Rev. Cecil Williams and other Black churchmen, Jewish Rabbis, as well as various Chritian priests and ministers, came away puzzled when they found that the average gurdwara bhai could not even speak English very well, let alone speak out publicly for the Sikh cause. The Sikhs had to come to grips with the flipside of the coin; that while a religion may take justifiable pride in being thoroughly democratic and egalitarian, with power vested in a sangat (congregation) rather than in a priestly hierarchy, in times of crisis it is very desirable to be ready with proper religious spokesmen. Then, when members of the press and other concerned Americans asked the Sikhs for helpful pamphlets to aid them in understanding what the Sikhs were trying to tell them, it became obvious that nothing appropriate for the Western reader had been published. This continues to be one of the unmet challenges facing the Sikhs in California (and elsewhere) three years after Operation Bluestar.

Meanwhile, the Indian government proceeded full speed ahead with its program of teaching the uppity Sikhs a lesson. With a total press blackout declared in the Punjab, Sikhs abroad were able to get little reliable information. What firsthand reports managed to come through to the outside were absolutely chilling. Bay area community newspapers largely reflected the government’s line, for example always referring to “Sikh terrorists”, never “Sikh freedom fighters” or even “unknown assailants”. National U.S. media were able to access only the Indian government’s official version of events; for the first time, many Sikh Americans got a shattering insight into the way news is packaged and presented, regardless of what the facts of a situation may be.

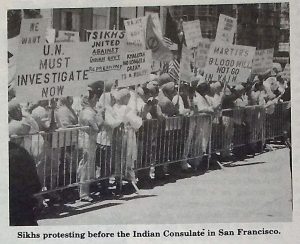

From the earliest days after Operation Bluestar, Sikhs in California came together to express their horror and outrage at the invasion, and to articuSikhs protesting before the Indian Consulate in San Francisco.

Late their alienation form the government of Indira Gandhi. An organization was soon formed, in cooperation with Sikhs in other parts of the country which was to be called the World Sikh Organization (WSO). Its construction was proposed in July, 1984, at a tumultuous meeting at Madison Square Garden’s Felt Forum in New York City. The constitution was later adopted at a follow-up meeting in Los Angeles. By now, many previously clean-shaven Sikh men were wearing beards and turbans, and many people took Amrit for the first time in their lives. The wearing of Kesari (saffron) turbans became de rigueur among patriotic Sikh men, and Sikh women found themselves leaving their saris in the drawer in favor of the Punjab salwarkameez. This sentiment is still prevalent today.

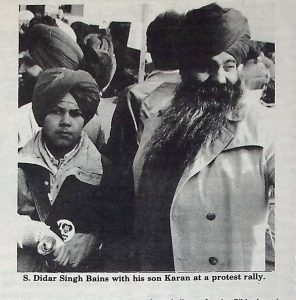

The World Sikh Organization got off to a strong beginning. Under the aegis of retired Maj. Gen. Jaswant Singh Bhullar, who claimed to have been sent by Sant Bhindranwale himself to organize the Sikhs abroad, the WSO took form and shape. Here in California, one of the far-reaching developments to come out of that session in New York was the establishment of a newspaper, the World Sikh News. Before this newspaper had even begun, however, two events occurred in Delhi which irrevocably changed the consciousness of Sikh worldwide: Indira Gandhi fell to assassins’ bullets fired by several of her bodyguards, and this became the signal for genocidal violence against Delhi’s Sikh community to begin. In orchestrated mob action planned by members of the Congress (I) Party, between five to nine thousand Sikh men, women and children paid for their faith with their blood. Press reports spoke of “hundreds” killed, and once again, as after Operation Bluestar, Sikhs in California and the rest of the country had to spread the word to the outside community that one must add another zero to any figures of casualties given out by the government of India. Many Sikhs in WSO, as well as other organizations, made concerted effort to approach to U.S. lawmakers to sensitize them to Sikh Concem. It was correctly perceived by these Sikhs that unless public opinion could be influenced, no’ real support would be forthcoming for the Sikhs. American opinion had rallied for the Blacks of South Africa and the beleaguered populations of various Central American republics; it was barely aware of the USSR sponsored genocide of Afghans, and unable or unwilling to be interested in the fate of another unknown exotic looking minority 13,000 miles away in a place of no strategic value to the U.S. And anyway, wasn’t India a democracy like the U.S.? And wasn’t the President of India a Sikh too, and lot of other prominent people there Sikhs as well? What was all the fuss about, anyway? Weren’t they really just another subspecies of Hindus after all? How ungrateful of these privileged Sikhs to keep burning the Indian flag in front of the Indian consulate on Arguello Blvd. in San Francisco! Sikhs had so many privileges in India! Weren’t they better off without that criminal element that had been flushed out of their temple? Ans so it went. There were demonstrations, speeches, more demonstrations, more speeches, interviews on television, radio, and in print. For most Sikhs it was the first time that they had been able to compare what they knew to be true by living it, with what was presented by the news media about it. No one ever took the six o’clock news at face value again. Again, the need was sharply felt for a local Sikh office of public relations; but now, nearly three years after Bluestar Operation, none exists here in Northern California.

Severe travel restrictions were imposed by the Indian government on Sikhs holding U.S. passports and who needed to go “home” for personal reasons, People, especially men, found that they could not obtain visas to attend a parent’s funeral, be with an ailing mother or father, or attend a son or daughter’s wedding. No explanation from the Indian consulate was ever tendered. Many Sikh ladies had to press on to India alone to settle: family affairs in Punjab. They were not immune to government harassment, however; the aged mother of a Los Angeles physician had her luggage searched at the Dlehi airport, and when the search yielded a few pamphlets published by an American Sikh organization, she was detained and spent a night in jail. As the Indian government continued to demonstrate its total lack of devotion to the spirit of true democracy, so the Sikh community in California and across the U.S. and Canada continued to believe that, at least, politics and religion are not separable after all, and that only in ‘their own sovereign state, Khalistan, could Sikhs be truly free. Older Sikhs who had suffered through the horrors of partition in 1947 shuddered to think of history repeating itself. Sikh who had condemned the Muslims for breaking away from Mother India in 1947 now found they disparaging Master Tara Singh and S. Baldev Singh and other leaders of that time for not pressing for a Sikh homeland when the time had been right. Bumper stickers in the parking lots of the gurdwaras in Fremont and El Sobrante ran heavily (and still do) to slogans such as “I love Sikh Homeland!” “Khalistan—our only choice” “Khalistan Zindabad” and others in similar vein. Inside the gurdwaras, particularly in Fremont, the names of the assassins Satwant Singh and Beant Singh are lettered in equal prominence on the walls with the original Panj Piaras. Sant Bhindrawale’s portrait in homes and gurdwaras all over is often larger and more imposingly displayed than those of Guru Nanak or even Guru Gobind Singh. While relations with the Hindu community definitely show predictable strains, overtures are made to the Muslim community. A Sikh Muslim Friendship Society is formed to appreciate points of common culture and history. Few, if any, Sikhs are seen marching in the recent NO AWACS FOR PAKISTAN rallies in California or the East Coast —instead “SUPPORT AWACS FOR PAKISTAN?” appears openly in some advertisements in World Sikh News. Sikh dancers no longer bound and leap to the rhythms of the Bhangra at Republic Day cultural programs, and one wonders if social gatherings will ever be free of certain undercurrents of strain which are inevitably felt.

These times of crisis for the Sikhs demand unity, a strong organization and the articulation of clear goals. This is a challenge for the Sikhs here in California, a challenge that they cannot afford to fail. Three years after Operation Bluestar, Sikhs must look objectively at themselves. Are Sikhs capable of unity after all? Or, are they determined to be perennially bogged down in ego exercises, Jats opoed to non Jats, Youth against old-timers? Can the Sikhs support a strong organization and see it through, regardless of which leader may come and go? The checkered history of WSO has some hard lessons for Sikhs if they are listening. Finally, do the Sikhs have clear goals? If so, why has so little progress been made after three years of trauma in the Punjab?

Bay Area gurdwaras are still showing the effects of too much political infighting. There are still mostly inadequate educational programs for young people. The level of paranoia is so high among Sikh groups or sangats that when anyone emerges from the ranks as a leader, others inevitably talks against the person, alleging him to have been planted by the Indian government, out for his own personal gain, or operating with any one of a dozen possible hidden agendas. There is pressure being felt now by the educated professional Sikhs in the Bay Area to provide enlightened leadership. Many people’ are coming together in meetings to address the burning questions that face the Sikhs. It is generally agreed that for any real progress to be made, the community grassroots must also be involved. Out of the aftermath of Operation Bluestar, one positive result has been the establishment of solid contact among Sikh groups all across the U.S. and Canada. People know each other now whose paths may never have crossed without the one catastrophic and (potentially) unifying event. Now events occurring in Punjab are usually quickly known by people in every Sikh community. World Sikh News has been a valuable asset to the community in these difficult times, whatever its many shortcomings may be.

It remains for the Sikh community to build itself up in strength and to move forward it is not enough just to be awake. Operation Bluestar awakened them; for the Sikhs to thumph, they must put aside all internal differences, and truly become the sons and daughters of Guru Gobind Singh, pressing forward in an organized way to realize the many rewards of self-determination.

Article extracted from this publication >> May 8, 1987