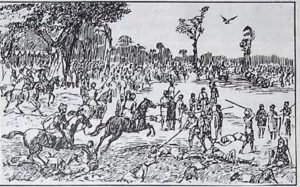

Morcha Guru Ka Bagh: A peaceful Morcha (agitation) was started in 1922 to emancipate the Gurdwara from the strange hold of Mahant, Sunder Das. This Morcha was one of the links in Akali agitation of 192025. The British colonial government extended its support to the Mahant in his designs and did not hesitate to order the police to beat them mercilessly with their lathes. The peaceful demeanor of the Sikhs against severe provocation evoked admiration all over “thy. World. From the September to November 17, the Sikhs continued to court arrests. Ultimately, the government relented. The demands of the agitation were conceded and the Morcha was withdrawn on November 17, 1922. In this Morcha 5606 arrests of the Sikhs were made. More than 1,500 Sikhs received injuries and over a dozen Sikhs were killed.

In order to show how the beating was done at Guru Ka Bagh, and how the Akalis conducted themselves, here is an eyewitness account given by Rey. CF. Andrews.

“I had opportunity of witnessing the scene at the Golden Temple itself, as they (Akali Jatha) came out with religious Joys written on their faces and a tiny wreath of white flowers placed on their black turbans which dedicated them to the sacrifice. I was able to see, also, in the city, the crowds of spectators, Hindus, Mussalmans, and those of every religion, welcoming and encouraging them, as they marched solemnly and joyfully forward, calling upon the name of God as their protector and savior. There, in the city, they were at the very beginning of their pilgrimage. Mile after mile of mud stained, waterlogged road lay before them. When I saw them on this first day of my visit, as they drew near to the end of their march, they were bespattered with mud and dirt, and perspiration was streaming from them; but their garlands of white flowers were still encircling their black turbans, they are still uttering with triumphant voice their prayer to God for protection, and the light of religion was still bright upon their faces.

“When I reached the Gurdwara itself, I was struck at once by the absence of excitement such I had expected to find among so great a crowd of people. Close to the entrance there was a reader of the Scriptures who was holding a very large congregation of worshippers, silent as they were seated on the ground before him. In another quarter there were attendants who were preparing the simple evening meal for the Gurdwara guests, by grinding the flour between two large stones. There was no sign that the actual beating had just begun and the sufferers had already endured the shower of blows. But, when I asked one of the passersby, he told me that the beating was now taking place.

On hearing this news, I at once went forward. There were some hundreds present, seated on an open piece of ground, watching what was going on in front, their faces strained with agony. I watched their faces first of all, before I turned the comer of a building, and reached a spot from where I could see the beating itself. There was not a cry raised from the spectators, but the lips of very many of them were moving in prayer. It was clear that they had been taught to repeat the name of God and to call on God for deliverance. I can only describe the silence and the worship and the pain upon the faces of these people, who were seated in prayer, as reminding me of the shadow of the Cross. What was happening to them was truly, in some dim way, a crucifixion. The Akalis were undergoing their baptism of fire, and they cried to God for help out of the depth of their agony of spirit.

“Up till now I had not seen the suffering it, except as it was reflected in the faces of the spectators. But when I passed beyond a projecting wall and stood face to face with the ultimate moral contest, I could understand the strained looks and the lips that silently prayed. It was a sight which I never wish to see again, a sight incredible to an Englishman. There were four Akali Sikhs with their black turbans facing a band of about a dozen police, including two English officers. They had walked slowly up to line of the police just before I had arrived, and they were standing silently in front of them, at about award’s distance. They were perfectly still: and did not move further forward. Their hands were placed together in prayer, and it was clear that they were praying. Then, without the slightest provocation on their part, an Englishman lunged forward with the head of his lathi which was bound with brass, He lunged it forward in such a way that his fist which held the staff struck the Akali Sikh, who was praying, just at the collar bone with great force. It looked the most cowardly blow as an every saw struck, and I had the greatest difficulty in keeping myself under control.

The blow which I saw sufficient to fell the Akali Sikh and send him to the ground. He rolled over, and slowly got up once more, and faced the same punishment over again. Time after time, one of the four who had gone forward was laid prostrate by repeated blows, now from the English officer and now from the police who were under his control. The others were knocked down more quickly. On this and on subsequent occasions, the police committed certain acts which were brutal in the extreme.

‘The brutality and inhumanity of the whole scene was indescribably increased by the fact that the men who were hit were praying to God and had already taken a vow that they would remain silent and peaceful in word and deed. The Akali Sikhs who had taken this vow were largely from the army. They were obliged to bear the brunt of blows, each of which was an insult and humiliation, but each of which was turned into a triumph by the spirit with which it was received.

“It was a strangely new experience to these men to receive blows dealt against them with such force as to tell them to the ground, and yet never to utter a word or strike a blowing returns. The vow they had made to God was kept to the letter. I saw no act, no look of defiance. It was a true martyrdom for them as they went forward, a true act of faith, a true deed of devotion to God.

“They remembered how their Gurus suffered, and they rejoiced to add their own sufferings to the treasury of their wonderful faith. The onlookers, too, who were Sikhs, were praying with them and praying for them, and the inspiration of their noble religion, with its joy in suffering innocently borne, could alone keep them from rushing forward to retaliate for the wrong which they felt was being done.

“A new heroism, learnt through suffering, has arisen in the land. A new lesson in moral warfare has been taught to the world.

*One thing I have not mentioned which was most significant of all that I have written concerning the spirit of the suffering endured. It was very rarely that I witnessed any Akali Sikh, who went forward to suffer, flinch from a blow when it was struck, there was nothing, so far as I can remember, that could be called a deliberate avoidance of the blows struck. The blows were received, one by one, without resistance and without a sign of fear. Rey. C.V. Andrews was, as we see, deeply moved by the noble ‘Christ like’ behavior of the Akalis. He apprised the Lieutenant Governor, Sir Edward Maclagan, of the brutality of the police. He persuaded him to see things for himself. Sir Edward Maclagan arrived at Guru Ka Bagh on the 13th September, 1922. He was deeply impressed with what he heard and saw. He ordered the beatings to stop. Arrests of Akalis began again. By then, about two thousand Sikhs had been beaten to unconsciousness and hospitalized.

Article extracted from this publication >> August 6, 1996