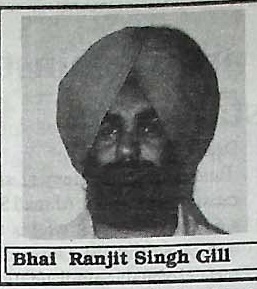

Ranjit Singh Gill and Sukhminder Singh Sandhu have been held in New York maximum security jail since May 14, 1987. Both of them are Sikh freedom fighters and wanted by Government of India Their extradition case is pending before a magistrate in New York. Before the extradition their attommeys have filed a motion for political hearing to introduce evidence that if they are extradited they will be subjected to torture extrajudicial execution. Magistrate James C. Frances IV in his ruling has denied this motion and has indicated that this is for the Executive branch (Secretary of State) to search the conditions of human rights in the country where they will be extradited. In his decision in fact Judge showed his concern regarding the human Rights violation. For the benefit of our readers we are publishing the entire text of magistrate J.C. Francis’s decision.

August 19, 1996, decision in Ranjit’s and Sukhminder case

MESSAGE

Magistrate Judge James C. Francis IV of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York August 19th handed down the accompanying traction in Ranjit’s and Sukhminder case. While the decision denies the hearing we requested on the ground that its grant is foreclosed by the case of Ahmad. y. Wigen in the Second Circuit, the decision contains some statements making clear that the magistrate judge, in fact, very much wanted to grant the hearing we sought.

Mary Boresz Pike and Ronald L. Kuby, who have represented Sukhminder Singh Sandhu and Ranjit Singh Gill since 1987, went together to the Metropolitan Correctional Center (MCC) in Lower Manhattan to tell their clients of the decision. Although not convicted of, or even charged with, any offense against U.S. criminal law, Ranjit and Sukhminder are held without bail and began their tenth year of incarceration at the MCC this past May. Upon leaving the prison after an almost two-hour consultation with their clients, Ms. Pike and Mr. Kuby reported that Sukhminder and Ranjit received the news of the decision with their customary dignity and equanimity. In a statement to World Sikh News, their lawyers sad, “Neither they nor we are the least bit discouraged by this decision. They understand, as will all who read it, that the Indian government is the real loser here. The human rights record of the Indian government has been revealed for the disgrace it is, Ranjit and Sukhminder recognize, also, that their case raises significant issues important to the protection of all refugees who flee persecution, and for that reason, they are committed to seeing those issues litigated, no matter how long it may take.” Messages of support will reach Ranjit and Sukhminder at the following address:

Ranjit Singh Gill 08443050 Metropolitan Correctional Ctr. 150 Park Row South, Fir.11 North New York, New York 10007 Sukhminder Singh 08442050 Metropolitan Correctional Ctr. 150Park Row South, Fir. 11 North New York, New York 10007 Memorandums and Order United States District Court Southern District of New York James C. Francis IV, United States Magistrate Judge

The government of India seeks the extradition of Sukhminder Singh Sandhu and Ranjit Singh Gill (the “respondents”) for the alleged commission of crimes in violation of the Indian Penal Code. The case has been assigned to me as extradition magistrate pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 3184. The respondents now renew their prehearing motion to be permitted to introduce evidence to demonstrate that, if extradited, they would likely be subjected to torture and extrajudicial execution.

Background.

This case has a long and remarkable history. Because the details are set forth in several prior opinions, I will only summarize them here. The respondents were arrested in the District of New Jersey in 1987, and extradition proceedings were conducted by Magistrate Ronald J. Hedges. Magistrate Hedges twice issued decisions rejecting requests of the respondents to conduct discovery. In re Extradition of Singh, 123 F.R.D, 108 (D.N.J. 1987); In re Extradition of Singh, 124 F.R.D. 571 (D.N.J. 1987). He also denied the respondents’ motion to submit evidence that if returned to India they would be subjected to human rights abuses, In re Extradition of Singh, 123 F.RD. 127 (DNJ. 1987). Following a hearing, Magistrate Hedges issued certificates of extraditability.

‘The respondents then filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus before the Honorable Robert W. Sweet, U.S.D.J., in the Southern District of New York where they ‘were now in custody. In the meantime, however, certain misconduct by the Special Assistant United States Attomey (“SAUSA”) who had prosecuted the case in New Jersey came to light. While those proceedings were underway, threatening letters seemingly authored by the respondents or their associates were received by Magistrate Hedges and the SAUSA. Subsequently, however, it was established that the SAUSA herself had written and sent the threats, (The SAUSA was subsequently charged with obstruction of justice in violation of 18 U.S.C. 1503 but was found not guilty by Reason of insanity.) Judge Sweet then held the habeas corpus proceedings in abeyance while the government moved before Magistrate Hedges to vacate the certifications of extraditability. See Gill vy. Imundi, 747F. Supp. 1028, 1036 (S.D.N.Y. 1990).

The habeas corpus proceeding before Judge Sweet was then resurrected. Throughout the extradition proceedings the government had relied in part on the confession of Sukhdev Singh. He had been charged in India with attempted murder and assault on police officer and conspiracy to commit terrorist acts, and the statement that he gave after his arrest implicated Mr. Sandhu and Mr. Gill A week before oral argument before Judge Sweet, however, the government learned that a year and a half earlier an Indian court had found the confession to be involuntary and untrue. Although this holding had become final, the Indian authorities had failed to bring it to the attention of the government attommeys here, Gill 747, F, and Supp. at 1037. Because consideration of the discredited confession tainted Magistrate Hedges’ finding of extraditability, Judge Sweet granted the writ of habeas corpus and ordered the respondents discharged from custody within thirty days unless his decision was appealed or the government filed new extradition complaints. Id. at 104347, 1050.

‘The government chose the latter course and filed the complaints that are subject of the current proceedings. Mr, Sandhu is charged in three counts. Count One charges, conspiracy to commit robbery and robbery of the Punjab National Bank in Ahmedabad, India. Count Two charges Mr. Sandhu with the murder and attempted murder of unarmed police officers and a magistrate in Udaipur, India. Count Three alleges that Mr. Sandhu conspired to rob and robbed the Chamber branch of the New Bank of India in Bombay, India. (The government of India has withdrawn Count Four against Mr. Sandhu, which charged him with the abduction of a police officer at a top Hill, India.) The complaint against Mr. Gill charges him with murder and attempted murder in connection with the deaths of a dian Parliament.

The new complaints were originally presented to the Honorable Kathleen A. Roberts, U.S.M.J, sitting as extradition magistrate, ‘The respondents moved before Judge Roberts to be permitted to introduce evidence that as political active Sikhs advocating an indo Punjab, they would receive inhumane treatment and be denied fair judicial process if extradited to India. Judge Roll denied the motion, holding that the doctrine of NonInguiry precluded the admission of such evidence at an extradition hearing. She reasoned that pursuant to [18U.S.C.] § 3184, an extradition magistrate has jurisdiction only to determine whether the crimes charges are covered by the extradition treaty as issue, that the persons before the court are those sought by the extradition request and whether probable cause exists that those requested) to be extradited committed the crimes charged. Inure Extradition of Sandhu, 886 F.Supp.318, 321(S: D.N.Y. 1993). Judge Roberts left the bench prior ‘You conducting an extradition hearing, and the case were reassigned to me. In anticipation of my holding the hearing, the respondents have renewed their motion. They rely principally on Gallina v. Fraser, O78 Ee 2d. 77 (2d Cir), cert denied, 364 U.S. 851 (1960). There the Second Circuit followed the rule of no inquiry but acknowledged that “we can imagine situations where the relator, upon extradition, would be subject to procedures or punishment as antipathetic to a federal court’s sense of decency as to require reexamination of the principle setout above. Id. at 79, the respondents make two primary arguments why the “Gallina exception” to the NonInguiry Tule should be applied here. (The respondents also incorporate by reference other contentions previously presented to Judge Roberts. I find Judge Roberts’ reasoning rejected those arguments to be persuasive. Further, her discussion of the underpinnings of the NonInguiry doctrine was comprehensive, and I will not repeat it here.) First, they contend that the underpinnings of the NonInguiry doctrine are absent because there is no bilateral extradition treaty between the United States and India, Second, they argue that the evidence of probable human rights Violations is so overwhelming that this cause is unique. I will discuss the respondents’ reasoning as well as the facts on which they rely in more detail below.

Article extracted from this publication >> August 28, 1996