How its world is changing. India used to champion anti-colonialism, non-alignment and third-world solidarity. It viewed China and Pakistan as the chief threats to its security, it fostered a special relationship with the Soviet Union, as the only country capable of deterring China, and it was suspicious of America, which was arming Pakistan as an ally against Soviet influence and expansionism.

But the cold war is over, and India’s traditional foreign policy is irrelevant. No longer can India play off the Soviet Union against the West to extort financial, military and trade concessions. The Non Aligned Movement, if not actually dead, is moribund (its present head, Yugoslavia, has turned in crisis not to its non-aligned brethren but to Europe); and third-world solidarity means lite when so many poor countries, including India, need the IMF more than they need each other, India’s policy-makers must clearly make a new policy.

The Soviet Union can no longer help. In the old days the Soviet Union saw India as a bulwark against Chinese and American influence in southern Asia; it gave India soft military credits for top of-the-line weapons such as Mig29s; it supplied oil and took payment in rupees; and in United Nations debates over Kashmir it supported India against Pakistan, Today the republics of the ex-soviet Union cannot be bothered with the local security concerns of India.

Soviet chaos has disrupted the supply of military parts, putting much of the Indian air force out of action, At the UN in November the Soviet delegate voted with Pakistan-and so against India-on Pakistan’s proposal to make South Asia nuclear free. India’s traditionalists are dismayed.

Not so India’s more open-minded. They see the benefits for India America, they surmise, no longer regards Pakistan as a strategic ally against communism but as a country with nuclear ambitions that aids separatists in the Indian states of Kashmir and Punjab, and favors Islamic solidarity with countries like Iran. Not only has America cut off aid to punish Pakistan for its nuclear program, so grounding many of Pakistan’s F16s for lack of spares, but it has accepted that the Kashmir dispute should be resolved through bilateral Indian and Pakistani talks and not, as Pakistan wants, through a UN-sponsored plebiscite.

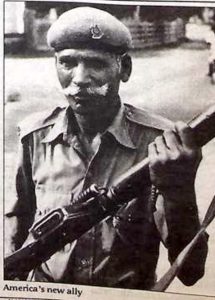

When Pakistan therefore accuses America of tilting towards India, a regional power with 850m people and armed forces of 1.3m, it is right. America and India have agreed on high-level exchanges of military personnel and are now talking about joint naval exercises in the sea lanes of the Indian Ocean something India never even discussed with the Russians.

However, both countries know that their common interest has its limits. The Americans see militant Islam as a threat but India, which banned Salman Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses” in deference to the 15% of its people who are Muslim, is not inclined to act firmly against such a threat. When the government of Chandra Shekhar allowed American aircraft to refuel in India during the Gulf war, it ran into political uproar (much of it from the Congress Party that rules today) and had to back down.

Nor can there be complete accord while America frowns on the spread of nuclear weapons, India and Pakistan have both become covert nuclear powers capable of assembling nuclear bombs at short notice, America can hardly insist on India’s nuclear virginity; this was lost as long ago as 1974, when India carried out its first (and only) nuclear explosion, What America wants instead is the good behavior outlined in Delhi by an American under-secretary of state, Reginald Bartholomew: agreements by India and Pakistan not to cross certain thresholds in weapons development, and a promise by India not to sell a nuclear research reactor to. Iran.

Although that sale would be covered by international safeguards, India has agreed to think again. In return, it may want an easing of the pressure on it to accept Pakistan’s proposal to rid South Asia of nuclear weapons. India has always objected to this because China is a nuclear power, and India wants the ability to retaliate.

However, the end of the cold war gives India and China the opportunity to be friends. Because India can no longer be seen as a Soviet proxy in South Asia, China has less incentive to give clandestine help with nuclear weapons and missiles to Pakistan-which means that India’s traditional fear of a China-Pakistan axis now looks out of date.

This will be reinforced on December 11, when Li Peng will be India’s humiliation in the 19 border war with China once it a matter of honor for all India parties to reject China’s territorial claims. However, Rajiv Gandhi visited China in 1988 and said the border was negotiable; today even the ultra Bharatiya Janata Party sees the advantage in becoming China’s friend. Both countries” could do with cutting their military spending on the Himalayan border.

A cut in India’s military spending might also reassure India’s neighbors in South Asia, which have long felt threatened by its size. Its inclination to act as the regional: cop has been welcomed by the Maldives, where Indian troops helped crush a coup in 1988, but resented in Sri Lanka, where President Premadasa last year ordered out Indian troops invited in by his predecessor. Throwing its weight around in the region has proved unproductive for India; it now concedes the need to substitute diplomacy for muscle.

Besides, with the cold war over, India needs to build its economic Strength if it is to matter politically. Since independence in 1947 India has followed a policy based on the Soviet model-and seen its share of world trade slump from 2.5% to 0.5%. At See The government of Narasimha Rao ” has seen the financial writing on, the wall and proclaimed that the economy will be opened up and foreigners wooed where once they were rebuffed. That may be just in — time, for the entire obsession with foreign policy, the main threats to India’s security come from inside, not outside, Secessionist groups are strong in Kashmir, Punjab and Assam, and religious strife between Hindus and Muslims is endemic. Escaping the problems of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia will depend less on diplomatic initiatives than on economic reforms.

(Economist)

Article extracted from this publication >> December 13, 1991