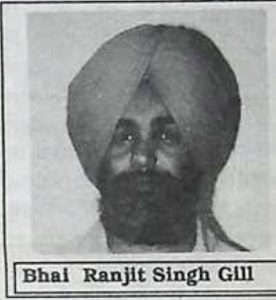

Two Sikh activists, jailed for nearly a decade while they fight extradition to India on militancy charges. Lost their latest bid August 19th, to get a federal court to investigate claims they face certain torture or death if returned home. While recognizing “compelling” evidence of likely abuse against the men, Sukhminder Singh Sandhu and Ranjit Singh Gill, Southern District Magistrate Judge James C. Francis IV, nonetheless, said the law requires such inquiries be left to the Executive branch, not the courts. Only the U.S. Department of State may examine conditions in a treaty country and deny extradition on humanitarian grounds, Judge Francis wrote, with reluctance, in the Matter of the Extradition of Sandhu and Gill, 90 er. Misc. Nol.

Mary Boresz Pike, one lawyer for Messrs. Sandhu and Gill, said she was disgusted by court’s ruling. Their next legal step: a court hearing on their extraditability that includes a review of whether there is probable cause that the men committed the charged terrorist crimes including alleged murders of police officers and a member of the Indian Parliament. “The Indian government throughout the entire history of this case has put forward evidence that is seriously flawed and has withheld evidence, and information,” said Ms. Pike, a Manhattan solo practioner. Judge Francis’s ruling is the latest setback for the men, both in their mid30s, whose legal odyssey has been marked by ups, downs and the bizarre. After they were arrested in New Jersey in 1987, a New Jersey magistrate judge the next year ordered them returned to India to face murder, robbery and other charges. The extradition was halted temporarily, however, when evidence emerged that a New Jersey federal prosecutor who handled the proceedings had falsified threatening letters to herself and the judge in the case. Ultimately, the prosecutor was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

Robert W. Sweet stopped the extradition altogether by granting a writ of habeas corpus to the men who have been imprisoned even longer than former Irish Republican Army member Joseph Doherty. Judge Sweet found the Indian government had withheld information that an Indian court had discredited a key statement from a codefendant implicating Messrs. Sandhu and Gill in various militant acts. He ordered the men discharged within 30 days unless his decision was appealed or the government filed new extradition complaints.

The government filed new complaints, excluding the discredited charges, which are pending before Judge Francis. Before a traditional hearing on their extraditability, the men sought a special inquiry into whether, as politically active Sikhs, they would receive inhumane treatment and be denied fair judicial process if returned to India. They cited a 1960 railing from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, Gall in a y. Fraser, 278 F. 2d 77, as providing room for exceptions to a general no inquiry rule when there is strong proof of likely abuse. They also argued the absence of a bilateral extradition treaty between the U.S. and India permits such a court inquiry.

Reluctantly, Judge Francis rejected both claims. He found the absence of a bilateral treaty no barrier because the U.S. and India have been observing the terms of a 1931 extradition treaty between the U.S. and Great Britain that covered the British colonies at the time including India, Australia and Canada. He found evidence of systematic abuse by the Indian government of Sikh activists a “far more compelling argument for relaxation of the rule of no inquiry” but not enough to overcome the leading Second Circuit case on the issue, Ahmad v. Wigen, 910 F. 2d 1063 (1990). He called Ahmed doctrine, which leaves pre extradition human rights inquiries to the Executive branch “absolute.”

In addition to Ms. Pike, Ronald L. Kuby of Law Office of Kunstler and Kuby, represented Messrs. Sandhu and Gill. Representing the government were Patrick J. Smith and Edward Scar alone, Southern District Assistant U.S. Attorneys, and Murray R. Stein of the U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.

Article extracted from this publication >> August 21, 1996