The community organises itself politically

IN the whirligig of Coalition politics on Capitol Hill. India with depressing regularity comes out a loser Injuly.an anti-Indian amendment to the Foreign Aid Bill narrowly missed being passed in the House of Representatives. Were it not for the intervention of Indophile and liberal Democrat, Stephen Solara, the Herger Bill, as it was called, was likely to have been approved.

Solarz lobbied I louse members against an amendment which as he says would have made $25 million in development assistance to India contingent upon whether some police officers were punished in a rape incident in Punjab.

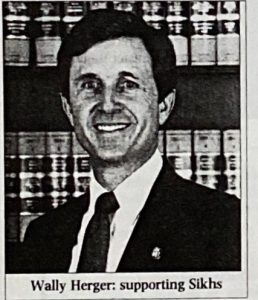

The vote was a close one: 212 to 204. Wally Herger a relatively obscure Congressman front Yuba City. California had enlisted the support of conservative Re-publicans ranged against India because of its support of Cuba its position on Afghanistan and its voting record in the UN. What was unexpected was the groundswell of bipartisan consensus on India’s alleged human rights violations in Punjab.

The controversial Herger Bill was it-self the work of the indefatigable Indian-American lobbyist. Gormeet Singh Aulak A former medical researcher at Harvard. Aulak is the president of the Washington-based Council for Khalistan. He found in Herger a ready ally. Herger’s congressional district includes Yuba City which has a large number of Sikh constituents including millionaire farmer Didar Singh. Last fortnight the new Indian Ambassador. Karan Singh made a firm move to counter the impression created about human rights violation in Punjab. He invited Thomas S. Foley, Speaker of the house Of Representatives to lead a congressional delegation to Punjab. And the Congresses-I MP. M.C. Mandan.. presented a letter to Foley signed by 58 MPs. protesting against such allegations made during the discussion on the Merger But it is becoming increasingly evident that in congressional circles. India the awakening Asian power, can no longer trade on the goodwill of being the world’s largest democracy. Last May there was little opposition in Congress or the Administration when India along with Japan and Brazil was labeled an ‘unfair trader’. In February Merger had been able to mobilise the support of 24 Congressmen to introduce an amendment that threatened to deny India the Most Favored Nation status unless if improved its human rights record in Punjab, which) Amnesty International alleged was poor.

Indian Embassy sources In Washington dismiss these developments as mere irritants, unlikely to affect what was an enduring upswing In Indo-US relations: They confidently recite the longand impressive list of agreements for cooperation in science and technology, Including collaboration on the Light Com- bat Aircraft, But clearly, they are uneasy The embassy is now frantically looking to hire a professional lobbyist to woo Capitol Hill Wilham Chasey who had offered the services of his Washington-based lobby firm tree of charge for a year has not been found satisfactory.

Part of the efforts to hire a lobbyist are to counter Pakistan’s consummate success in working the public policy process of competing interests General Zia s Pakistan had enlisted the services Denis Neil & Co to broker a compromise formula in 1987 which would secure congressional support for the S4.2 billion and package without any fresh constraints on its nuclear programme Now, Benazir Bhutto has brought in a friend from her Radcliffe days. Mark Segal.

But in a world of intensive lobby politics, where professional lobbyists are necessary, does India have the resources to stay on the inside track: More sound system where every third lobbyist in Washington is in the pay of a Japanese company. Most observers believe that a cheaper and more effective way is to mobilise the thousands of highly skilled.

well-paid professional Indian-Americans. It is a message that Solarz has been seeking to impress upon the Indian- American community here. Addressing a recent fund-raiser in his honor in California, Solarz said: “I think the time has come for the Indo-American community to shape US foreign policy in India.” Describing the community as a “vibrant and increasingly vigorous factor in American politics”, Solarz told INDIA TODAY “The community has not yet woken up to its full potential. But when it does it can be counted upon to exercise a political clout far greater than their number would suggest. A disproportionately large number of Indian-Americans are highly educated relatively well-paid professionals.”

The 48-year-old Democrat from Brooklyn, a predominantly white Jewish constituency, Solarz has amply benefited from the political emergence of the Indian American. As chairman of the sub- committee on Asia, he has been singled out for his steadfast commitment to better relations with democratic India. An exasperated Zia-ul-Haq once called Solarz, “the voice of India’. Says Solarz: “He meant it as a criticism took it as a compliment.”

Such a stance has won him many generous Indian-American admirers— who have contributed handsomely to his election funds—headed by California cardiologist Virendra Bisla. Moreover, it is not at all unusual for Solarz, garbed in a sherwani, to raise thousands of dollars at fund-raising meets organised by Indian- Americans. His appearance at the California fund-raiser on July 22 netted him $16,500.

BUT even without Solarz’s exhortation there are signs that Indian-Americans are starting to organise themselves politically. The most visible example is the Indian American Forum for Political Education (1AFPE). The moving force behind the 1arre and the wider Asian American grouping, the Asian Voters Coalition is Joy Cherian, currently the highest ranking Indian-American in the Bush Administration Cherian, 47, an immigrant from Cochin, is the equal employment opportunities commissioner, a sub-cabinet rank equivalent to an assistant secretary of state.

Flanked by what suspiciously looked like a red chillies shrub on one side and a curry leaf plant on the other, Cherian spoke about taking the Indian community first to “Capitol Hill, then the White House and now the Supreme Court”. When 1Arpe was created in 1983, its members had virtually to drag congressional representatives to attend their annual reception. Today five years later, the reception held by them boasts of attendance by such figures as Senator Edward Kennedy, Paul S. Arbanes, John Warner and Rudi Boswitz.

Cherian has a vision an Indian- American community, modelled on the Jewish-American lobby. He told INDIA TODAY: “In the case of Polish-Americans, an American President makes a statement on Solidarity in Michigan. We will have come of age when, similarly, an American President will find it politically opportune to make a policy statement on India before an audience of Indian- Americans.”

Yet can the Indian-American com- munity hope to achieve any real political clout when it numbers barely | million (according to the 1980 census) or just 0.2 per cent of the population? In at least two states, they are already large enough in numbers to make a difference. Around 17.5 per cent of the population of Indian- Americans are in New York state and 15.4 are in California. Their strength is now such that they are an important electoral consideration. “In a tight election, Asian votes can swing votes in key electoral states like California and New York,” says Cherian, former chairman of the Asian Voters Coalition.

But there is another problem, as Gopal Sivaraj Pal of Virginia, a founder-member of the IAFPE, points out—the division of opinion within the Indian-American community. Indeed. a quick survey of the 310 Indian-American organisations shows that it was open to question whether there was any validity in using the term ‘Indian-American’ as denoting a homogeneous grouping. Divisions within the community were embarrassingly evident at last year’s Republican National Convention when Indian-Americans held three different receptions.

Only too aware of this political weak- ness, Cherian in his farewell presidential address to the 1arre, admonished the community for behaving like divided Indians on the narrow basis of “back home identities” with hyphenated American status. Moreover, while middle class professionals may have become more unified during their stay here, Amrita Basu in her recent study on Indian immigration, indicates that new immigrants are likely to have stronger regional, linguistic and ethnic identities. “There are fewer professionals. They are from small towns, they like to be self-employed and are, thus, isolated from the pressures to conform to mainstream America.” she says.

Moreover, less than 20 per cent of Indian-Americans are registered as voters and the dominant mood of the community remains politically apathetic. For most, a reception thrown by the Indian ambassador is far more of a draw than that by their local Congressman.

There is, however, an undeniable drive amongst the older, first generation immigrant’s well-placed professionals between 35 and 45 years, who are keen to participate in the political process. They provide the backbone for the four major umbrella associations that have increasingly come to represent the political interest of the Indian immigrants: the